The drive from Dhaka to Daulatdia took around three hours, which was plenty of time for my colleague to brief me about what to expect when we arrived. Located in Bangladesh’s Rajbari District, Daulatdia is not far from the border with India, and it is infamous for being the country’s – and one of the world’s – largest brothels.

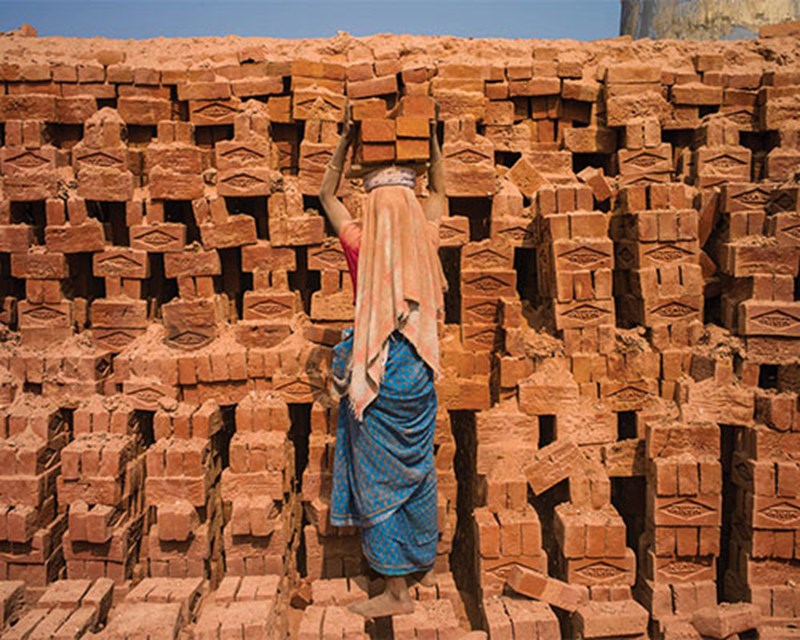

As many as 1,800 sex workers and some 500 children live in the densely-packed village close to the banks of the Padma River. Intersected by a railway line, the community is a labyrinth of concrete blocks, brick buildings, and tin huts. Around the cramped and dark working rooms, there are shops of varying sizes, where clients gather on benches, among hawkers and rickshaw drivers. Living conditions are squalid and drug use is common.

In Bangladesh, sex work is legal only in licensed brothels. Workers must be over the age of 18 and are supposed to hold a certificate stating they consent to the work, but a high proportion have been illegally trafficked into the industry.

As CEO of the Freedom Fund, which works to end modern slavery by identifying and investing in the most effective frontline interventions, I was in Daulatdia to learn more about the commercial sexual exploitation of children, or CSEC, and find out what my organisation can do to help those affected.

Bangladesh, once one of the world’s poorest countries, has made great economic strides and in 2015 achieved lower-middle income status. Yet, according to the World Bank, more than 20 million Bangladeshis remain below the poverty line (living on a daily income of less than US$2.15).

Many children are forced to drop out of school to earn a living, and only a quarter of Bangladeshi girls complete secondary school. This leaves them highly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, and thousands find themselves exploited, trafficked, and trapped in the commercial sex industry.

The women we met on our visit to Daulatdia were in a desperate situation. The brothel was locked down for months in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the workers’ income dried up overnight. Few women had any savings, and many were left destitute, reliant on meagre government handouts to eat until business resumed.

Even after the restrictions were lifted and the women were vaccinated, business has remained slow, because a new, faster highway means fewer truck drivers are stopping in Daulatdia.

According to local NGOs, as many as half of those working in the community’s brothels are believed to be under 18. Like adult sex workers, they are regularly subjected to violent abuse and coercive behaviour, with many being exposed at an early age to sexual activities, gambling, violence and drugs, as well as molestation and sexual abuse by clients. In some instances, children are also brought into the brothel from other communities and managed by pimps to work as bonded sex workers.