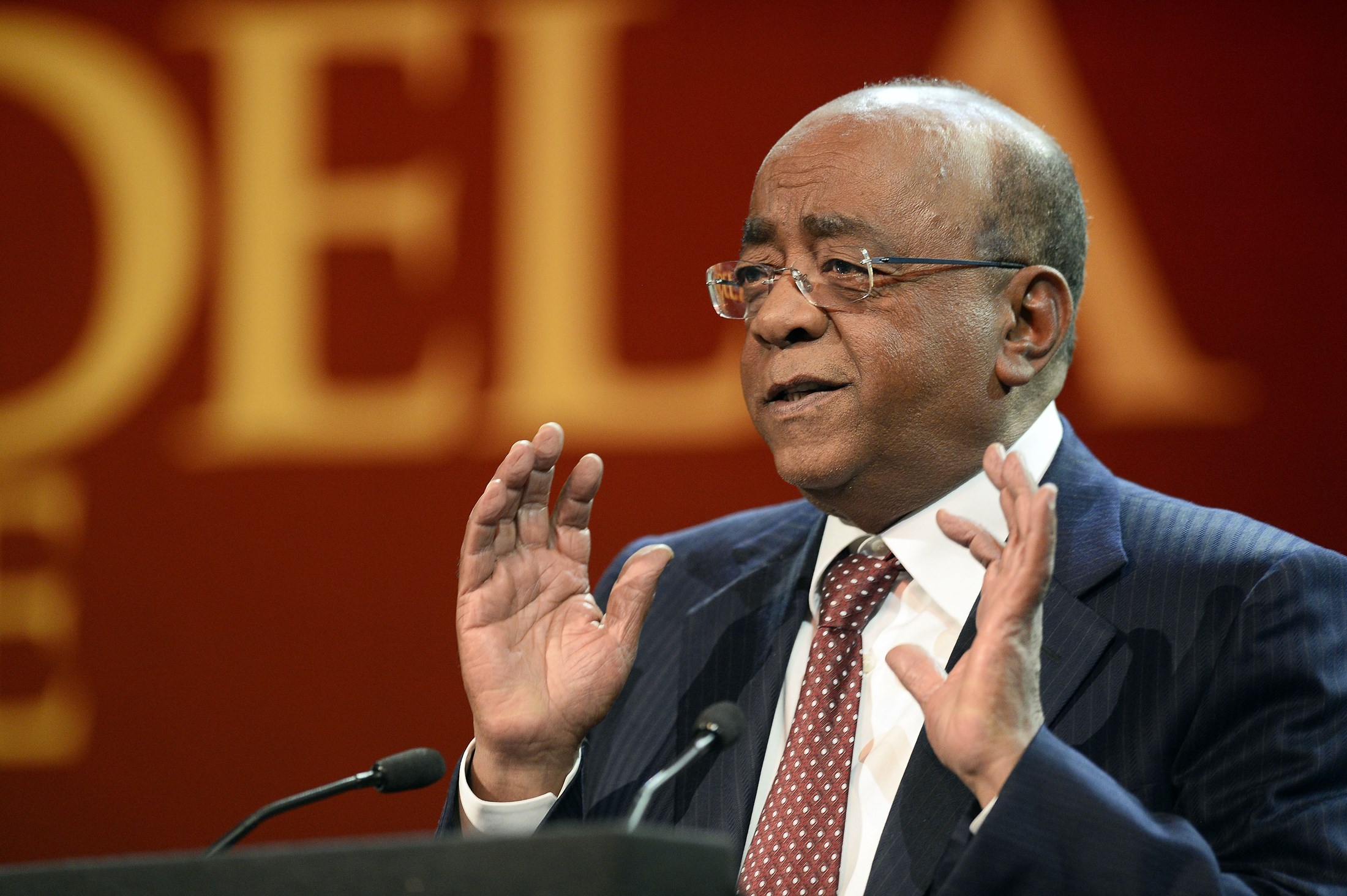

People ask, ‘how much have you achieved?’ And I don’t know, maybe very little, but at least I’ve tried. If you can just move things a few inches forward that’s great, because I’m sure a lot of other people are also helping to move that big animal forward.”

The ‘big animal’ to which Mohammed ‘Mo’ Ibrahim refers is no less than the reshaping of government in Africa, the continent of his birth and the passion of his life. Through his eponymous foundation, he has worked for more than a decade to foster democracy and build pressure for better, less corrupt leadership – and in doing so, has helped raise expectations and outputs across the region.

Today the Mo Ibrahim Foundation is considered the preeminent independent voice on governance in Africa. Ibrahim, meanwhile, is a magnetic presence, all exclamation and exhalation, at once galvanised and exasperated by the pace and direction of change on the continent.

“We don’t lack resources, we don’t lack land, and we don’t lack space, so what are we doing?” asks the Sudanese-born philanthropist. “Nelson Mandela [South Africa’s first black president] put it beautifully when he said that Africa is a rich continent, but the African people are poor. That for me was an amazing statement; it just slaps you in the face.”

As founder of mobile phone operator Celtel, Ibrahim spent decades travelling the continent, working within and across byzantine power structures in both the public and private sectors. He became convinced of the value of strong institutions and the rule of law – and for a country’s leaders to inspire, not hinder, development.

“Good governance is really about institutions and the way the country is run,” he explains today. “Leadership is about vision, those rare leaders who can really transform a society.”

Ibrahim himself cannot be accused of a lack of vision. Having sold Celtel in 2005, in 2006 he launched a range of initiatives designed to foster good governance and reward superlative leadership.

The most high profile is the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, which ranks government effectiveness across the continent. Established initially with the John F Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, the index tracks 58 criteria in five main categories.

A country’s score reflects how well it is providing services to its people – and nobody likes to be told publicly that they can do better. Upon its publication in 2006, the inaugural index was greeted warily in the corridors of African power.

“The body language was not friendly,” recalls Ibrahim. “But nobody criticised us for doing it because people could not find an angle. We are Africans so nobody could accuse us of being colonialist. We are using our own money, so they could not say we were agents of the CIA. And we have no outside incentive because there’s no political or financial motivation for us to do this.”

It was not uncommon for disgruntled leaders to pick up the phone and complain to Ibrahim directly, to which they would receive a straightforward response: “I don’t write it.”

The data is compiled from the foundation’s own measurements as well as 34 other sources. Every digit is indexed, every decimal point referenced against its source. And while Ibrahim insists leaders are welcome to contest the figures, “in 10 years we have not changed a single number”.

Today the index is both a benchmark and an incentive. A team headed by Abdoulie Janneh, the former under-secretary-general of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, spends its time flying from capital to capital, meeting with government leaders and discussing a country’s ranking.

It helps that major global donors – from USAID to the UK’s Department for International Development – use the index to aid in the disbursement of billions of dollars annually. A high score, then, can bring high reward.

“Countries accept that we’re not using the index to criticise any one government,” says Ibrahim. “We say, ‘This is the outcome of your policies; are you happy or is there something you need to change? And by the way, this is how your neighbours performed in all the same areas’.”

The benefit of this objectivity, Ibrahim notes, is that “it’s not a shouting match. It’s not personal or down to tribal or religious background. It’s down to achievement.

“It is not acceptable that leaders just rely on good speechwriters to sell whatever,” he adds. “It’s not about nice phrases or rhetoric or personal charisma. It is time to talk numbers, to talk facts."