In 2015, Prince Alwaleed bin Talal made headlines when he announced he would give his entire wealth to philanthropic causes. The news, given in a press conference in Riyadh, marked a turning point for giving in the Middle East – not least because of the sum involved; an astonishing $32bn. In that moment, Alwaleed became the first Muslim Arab to make such a landmark pledge, redrawing the boundaries of giving in a region already known for its generosity.

The Saudi royal has long been a major donor to causes around the world. This year alone, Alwaleed has pledged $1m to aid victims of twin earthquakes in Japan and Ecuador and a further $1m to the thousands affected by flooding in Sri Lanka. To date, his aid has reached people in 120 countries.

But it is his $32bn pledge – and the creation of a new master vehicle, Alwaleed Philanthropies (AP), to support it – that has, for the first time, pushed his philanthropy into the international spotlight.

The reality is that little has changed in the prince’s approach, but the pace has certainly quickened. Fellow Saudi royal, Princess Lamia AlSaud, the new secretary general of AP, quotes the aspirations of her chairman, when she says: “After 35 years HRH says he is only taxiing; we haven’t taken off yet.”

The stated mission of AP is to build bridges and move towards a better, more tolerant world. It seeks to foster cultural ties through education, to develop communities, and empower women and youth.

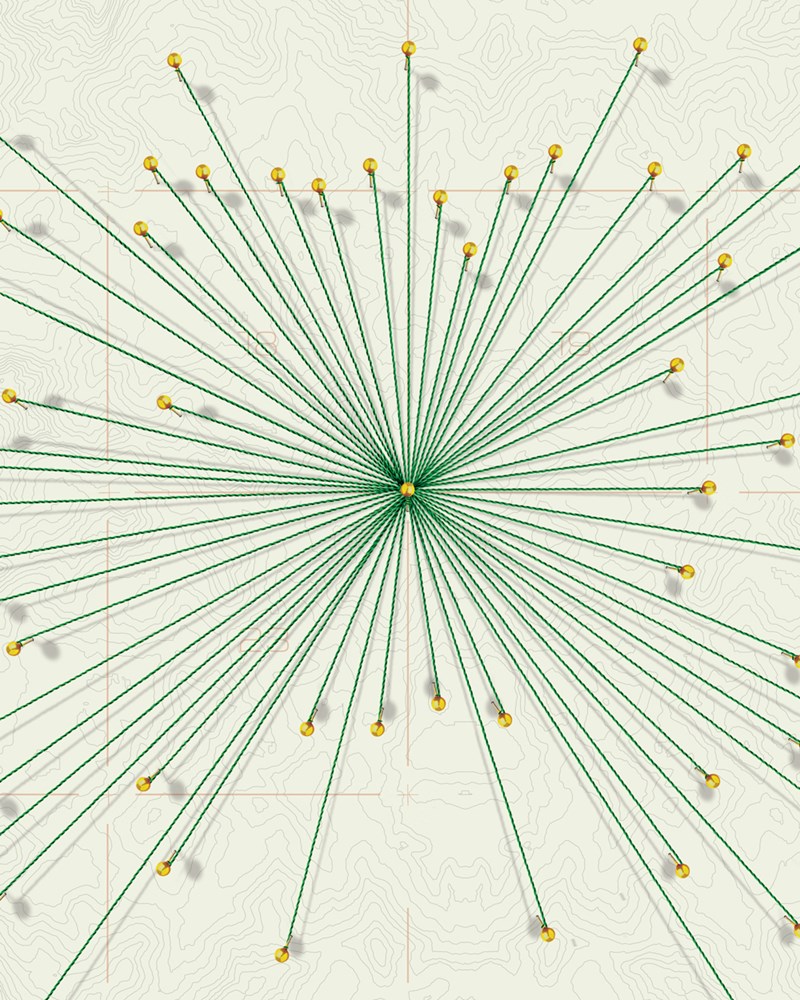

It also aims to provide relief in times of catastrophe. All of these strands are already work in progress. In the words of its founder: “Humanity has no religion, no race, no gender. That’s why the radius of our contribution will cover the whole world, and not just one region”.

AlSaud describes the prince as a role model. “I hope that his pledge will encourage and inspire others.”

The $32bn gift will, she says, be given during his lifetime, with the amounts given by his businesses increasing gradually, but working to a schedule.

“We want his businesses to keep growing for obvious reasons,” she says, smiling. Already, there are 100 million beneficiaries worldwide.