The science of progress

Science and technology should reach the poor first. Yet, in practice, what I’ve found is the opposite. It’s not fair and it’s not acceptable.”

From her office in Jeddah, Dr Hayat Sindi is railing at a system in which she says the benefits of science go to improving the lives of those who can afford it, rather than those with the greatest need. Innovations that could transform the lives of the world’s poorest people, she says, all too rarely reach them.

“I believe science and technology has the power to make a huge difference in people’s lives: for me it’s magic,” she explains. “But we need to ensure it reaches everybody.”

Sindi’s day job is to do just that. As chief advisor to the president of the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) on science, technology and innovation (STI), she is spearheading a push to put tech-driven advances at the heart of development work in the bank’s member nations.

This means not only exploiting innovations to drive down poverty, reduce inequalities and improve livelihoods and health – but creating a climate in which low-income nations have the scientific ecosystem and expertise to design their own solutions.

“We want to mainstream science, technology and innovation, not just within the bank, but in member countries – and especially the least developed,” says Sindi. “If we want renewable energy, if we want low-cost diagnostics and clean water, science has to lead the agenda.”

The IsDB has the clout to help make this a reality. The bank has 57 member states across four continents, giving it access to a fifth of the world’s population; operating assets of $16bn and subscribed capital of $70bn. It is a major lender to much of the Muslim world, where it has historically been a passive funder of infrastructure projects – a strategy that has been overhauled by current president Bandar Hajjar.

“He wanted to shift from being a development bank into a bank of developers,” explains Sindi, who joined IsDB in 2017 after being headhunted by Hajjar to lead IsDB’s new strategy. “The model around the sustainable development goals [SDGs] gave us a focus, and then a target to see our member countries achieve them by 2030.”

Breaking barriers

Hayat Sindi knows first-hand the transformative potential of science. Born to a conservative family in the Saudi province of Makkah, as a young woman she broke the mould by traveling alone to the UK to study pharmacology at King’s College London. Later, at Cambridge University, she became the first female from the GCC to obtain a PhD in biotechnology.

Since then, she has racked up an array of roles and accolades. Following studies at Harvard and MIT, she went on to establish multiple businesses, among them Diagnostics for All, a social enterprise that deploys low-cost diagnostic tools to alleviate disease in developing countries.

A former UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador, she is also one of the first women to serve on Saudi’s Shura Council, an influential body that advises the government.

As the IsDB helps member nations ramp up their investment in science and technology, she hopes to see female scientists gain in stature and visibility.

"When I was a child looking at pictures of scientists and scholars, I told my father, 'I can't see anyone looks like me', she says. "He would say, 'Hayat, with education, you can do anything.'"

“If a country has the right infrastructure and know-how, it can find its own solutions to its own challenges.”

This shift has seen the IsDB put new emphasis on conceiving and designing projects that are sustainable, scalable and STI-led. It is also taking a lead role in encouraging the open sharing of research and ideas across member nations, and in seeding platforms where innovation can flourish.

The premise, says Sindi, is that if the bank can help shrink the gap on scientific invention and technology between developed and developing countries, it can also begin to close the gap on poverty, health, job creation and more.

“If a country has the right infrastructure and know-how, it can find its own solutions to its own challenges,” she notes.

Achieving this is no small task. The IsDB’s member list includes some of the world’s poorest and most precarious nations, where R&D is an afterthought to more pressing issues such as hunger, disease and governance.

According to data from the World Bank, for example, Niger has just 26 researchers per million people and Mali 33. This compares to about 8,000 in Denmark and 6,800 in Singapore. And where innovations do emerge, supply chains may not follow – in large part because the consumers who would benefit most can’t afford to pay market prices for a new drug, app or other invention.

The IsDB’s answer to this is three-fold. It plans to empower entrepreneurs in its member states with funding, mentoring and training, seeding a pipeline of bright, young innovators with a clear grasp of local challenges.

Alongside this, it is working to help countries build policy frameworks that will fuel science and technological innovation. Lastly, it has reframed its own business model to favour projects where knowledge transfer from advanced nations is part of the deal.

Sindi offers an example of the bank’s partnership with India-based nonprofit the Barefoot College. Here, 40 illiterate and semi-literate women in nine IsDB member countries – many of which are at the sharp end of climate change – were trained as solar engineers.

Newly equipped with technical skills and the means to earn a living, these trainees are on track to provide more than 2,000 homes in impoverished rural communities with clean, low-cost lighting over the coming years.

“This is a simple project, but the wider impact is huge,” says Sindi. “We are empowering women, some of whom never went to school, so they can become entrepreneurs. And at the same time, we're building community resilience, and helping to protect against climate change.”

The long-term goal is to see countries build out strategic industries in which they can gain a competitive advantage, weaving domestic firms into global value chains. These chains are a key driver of trade and poverty reduction in developing countries, with those that participate in them (such as China, Bangladesh and Vietnam) seeing breakthrough income growth and productivity.

“It’s not about single projects any more, but creating a wider environment,” says Sindi; “how are we able to help with implementing a fourth generation of industrialisation? That’s the role of the bank now: focusing on giving countries the tools to help them excel.”

Right now, Covid-19 is front and centre in the IsDB’s thinking. The lender unveiled a $2.3bn aid package earlier this year, designed to help bolster member states’ efforts to fight the pandemic and fend off its impact on their economies. By May, $1.86bn in assistance had been pledged to 27 countries, ranging from funding the purchase of medicines in Tunisia, to kitting out clinics and ambulances in Cote d’Ivoire.

Sindi describes the pandemic as an inflection point for development, with actors such as multilateral development banks, governments, aid organisations, philanthropists and the private sector needing to work collaboratively now more than ever.

In an op-ed published earlier this year, IsDB president Bandar Hajjar noted the pandemic was an opportunity to “do development differently”, to shape markets rather than react to market failures, and to invest in science and technology as a buffer against future crises.

“We can forge Public-Private-Philanthropic-People-Partnerships to ensure both citizens and economies are going to benefit,” he wrote.

In this, the IsDB is trying to lead from the front. Applications for the 2020 round of the bank’s Transform Fund specified that entries should offer solutions to Covid-19-related issues that would benefit local communities – be that digital disease surveillance, or low-cost rapid tests and screening methods.

Transform, and its sister platform Engage, are part of IsDB’s bid to turn from being a bank of development, to a bank of developers. With an initial target size of $500m, the Transform Fund aims to cultivate innovators and entrepreneurs able to solve problems in their home countries.

It does this by providing scientists, innovators, start-ups and institutions with funding for early-stage ideas, or growth capital to scale up or commercialise projects. Over time, the goal is to spur a new wave of development solutions.

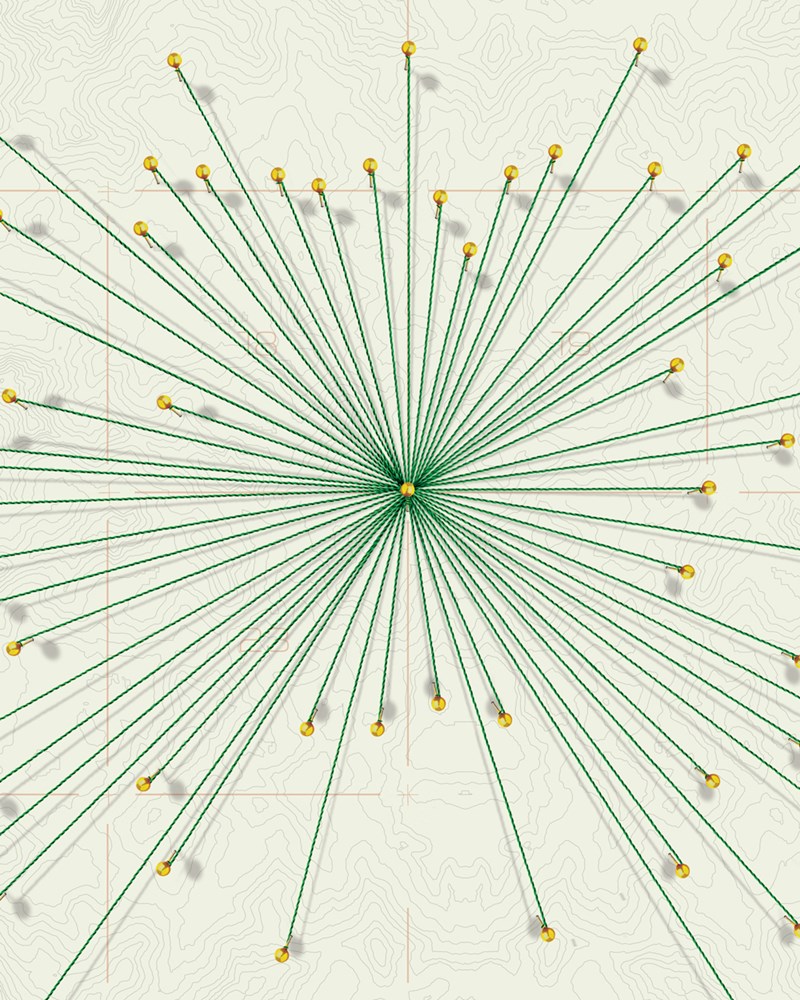

Pivotal to Transform is the promotion of capacity building and cross-sector partnerships; a vision that also underpins the bank’s Engage hub. Launched in 2018 to accelerate progress towards six key SDGs – including zero hunger, clean water and sanitation – Engage connects scientists, NGOs, entrepreneurs, the private sector, and others to market opportunities, funding – and each other.

IsDB wants the hub to be a digital incubator, explains Sindi, spreading ideas and technologies among innovators around the world. “We need the best ideas, we need the best technology, and we need open science and open innovation, because no one can do it alone,” she says.

Early grantees are showing promise. Among them is an initiative designed to improve sanitation and water treatment in an impoverished part of Jordan, home to many Syrian refugees. Led by German nonprofit Borda, and funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, the project will see the development of a sustainable community sanitation system in the town of Azraq.

The project is supported by a $150,000 grant through Transform, and aims to maximise the reuse of water, cut unsafe sanitation practices and create better living conditions for local populations. The IsDB funding will help build local capacity for the future running of the sanitation system, which is earmarked to be a model for replication elsewhere in Jordan and the wider region.

Another grantee, Taleb Al-Tel, a professor at the UAE’s University of Sharjah, won funding for his research on the development of new treatments for multidrug-resistant superbugs. In Bangladesh, a project to develop jute-based housing for displaced families in Rohingya refugee camps, earned support to scale its work.

“We’ve seen some amazing ideas that could help [member] countries in everything from diagnostics, to sustainability, to agriculture,” says Sindi, “ideas that could then be duplicated in adjacent countries.”

“Achieving the SDGs will require trillions of dollars. But the money is there, it is just a question of mobilising it.”

A sticking point is finance. Change at scale requires funding – and for countries with limited means, this can be in short supply. This can make it difficult to grow and commercialise ideas, or to gain enough traction for large-scale impact.

Development actors are increasingly eyeing blended finance – a mash-up of public and private capital – as a way to respond to social and economic challenges, and fill the funding void.

The IsDB is ahead of this curve, says Sindi, pointing to the lender’s ‘five Ps’ model; otherwise known as Public-Private-Philanthropic-People-Partnerships. The strategy forms part of the bank’s experimentation with innovative financing tools, bringing diverse partners together to pool resources and unlock growth.

“Achieving the SDGs will require trillions of dollars. But the money is there, it is just a question of mobilising it,” says Sindi. “[Development] projects have to be bankable, that’s a given, but it also means we need all stakeholders to play their part.”

Partners against poverty

The IsDB’s Lives and Livelihoods Fund is an ambitious example of concessional financing. Launched in 2016 with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and backed by outside donors, the fund is the largest development initiative of its kind in the region.

The $2.5bn fund provides cheap loans to the IsDB’s poorest member countries to finance poverty-alleviation projects in areas such as health, agriculture and infrastructure. Donor grant money – raised and matched by the Gates Foundation – is used to reduce the interest payment on loans, putting them within reach of even the most impoverished nations.

Since rollout, the value of the fund’s approved projects has surpassed $1bn, expanding in geographical scope from West Africa, to sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

As part of the IsDB’s efforts to widen its base, the bank last year joined forces with UNICEF to establish the Global Muslim Philanthropy Fund for Children, a Sharia-compliant platform for high-value donors designed to drum up new funding for children and youth.

Targeting areas such as education, health and early childhood development, the fund allows multiple forms of Islamic giving – such as zakat, sadaqah donations and waqf endowments – to be used to finance aid and development work. Grants are disbursed to UNICEF and IsDB initiatives in Muslim countries.

The fund counts the UAE’s Abdul Aziz Abdulla Al Ghurair as an anchor philanthropist, following his $10m pledge in 2019. The money will support the education of refugee children in the Middle East and North Africa, Sindi said.

The bank is also pushing to tap Islamic finance, with projects such as its One Wash Fund, a tie-up with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

Unveiled in 2019, the fund will invest in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) projects in member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), with the goal of combating cholera and other diarrheal diseases. By 2030, it aims to have slashed cholera-related deaths by 90 per cent in the worst affected OIC countries.

The fund will be capitalised by a combination of charitable donations and the proceeds of an impact sukuk, designed to appeal to Islamic investors. The proceeds of the sukuk will be used to finance the WASH work, with investors repaid by outcome donors – if the programme hits its predefined results.

For Sindi, these are all pieces of the same puzzle: sourcing new ways to find, fund and scale solutions that can improve the lives and wellbeing of some of the world’s poorest – and bring the SDGs within grasp. Giving nations on the front lines of development problems the means and know-how to tackle them can be game-changing, she argues, not only for their populations, but also for the wider world.

“What motivates me is that I know science can make a difference,” she explains. “Science doesn’t care for boundaries, gender, nationalities – those distinctions dissolve there. Change requires persistence and it is challenging, but I believe we can succeed.” – PA