Saudi Arabia is no stranger to large-scale largesse. Both the government and individual donors give generously and frequently. Yet the infrastructure of giving – from foundations to the nonprofits on the ground – has struggled to play in the same league.

The Riyadh-based King Khalid Foundation (KKF) is one agency seeking to redress the balance. Founded in 2001, KKF aims to help cultivate and scale the country’s fledgling nonprofit sector to meet national challenges and lobby for socioeconomic change. And while there is still much work to be done, says director general Princess Banderi bint Abdulrahman AlFaisal, change is underway.

Q. KKF has a broad mandate. How do you gauge your success?

We set out to change the face of philanthropy in Saudi Arabia, and if you look at where the sector was 10 years ago, it is enormously different today. When we began even the term ‘nonprofit sector’ was unknown. About four years ago, in the second of our annual development debates, we talked about the underrepresentation of – and lack of consultation with – the nonprofit sector in the kingdom’s National Development Agenda. The Ministry of Planning was sceptical, but over time we convinced them to include us in discussions.

Today, the nonprofit sector is front and centre in the government’s economic plan, Vision 2030, and we’ve been asked to contribute to policy planning. The nonprofit sector currently accounts for less than 1 per cent of GDP and the goal is to increase that to 5 per cent by 2030. So the government has absolutely bought in to the work we are doing.

Some elements of our work are difficult to measure. If we are working on youth employment, for example, gauging impact is easy: we can track how many candidates got jobs and stayed in those jobs. Other aspects of our work are less tangible, but I’ve no doubt KKF has played a key role in driving change in our industry.

Q. How has KKF’s own approach changed since its inception?

We’ve learned through trial and error. The foundation started as a grantmaking organisation – initially we wanted to work with local partners in rural communities on development projects. We failed miserably; we were talking different languages. KKF talked about sustainability and impact, while the nonprofits focused on cash handouts and charity. As a result, we stopped all grant activity and for the next two years focused on building the capacity of local NGOs and helping to change mindsets.

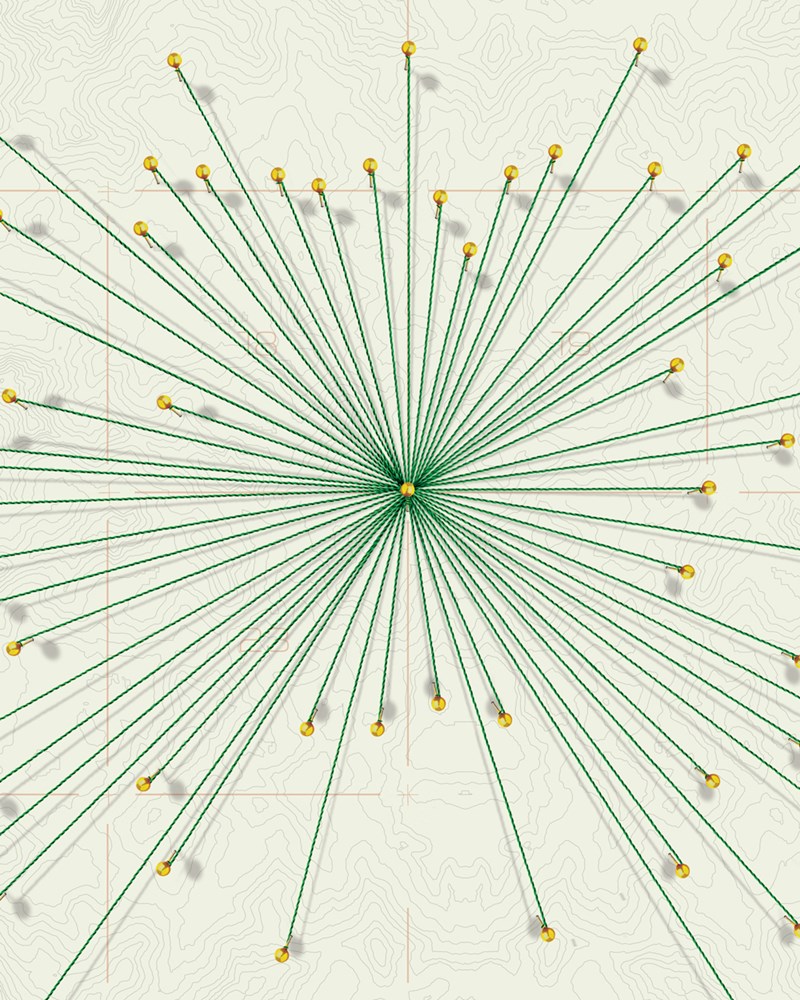

That was 10 years ago. We gradually reintroduced grants, which today comprise more and more of what we do - in just two days this week, we’ve signed 20. Grants are typically between SR100,000 (about $26,500) and SR750,000, but ultimately it’s about the quality of the grants rather than their size. Many local organisations don’t know how to apply for a grant, draw up an action plan or a budget, or report back. We want them to develop those skills and will help them to do so. We believe our approach means nonprofits will be better prepared to fundraise in future.

I have changed a lot, too. My father challenged me to be ambitious and give back, but while I certainly wanted to be involved with the foundation, I didn’t want to be the boss – I was slightly bullied into taking it on. Over the years, I’ve learned more from our failures than our successes.

I’ve also learned that leaving your ego at the door, as a person or as an organisation, goes a long way to developing successful partnerships.