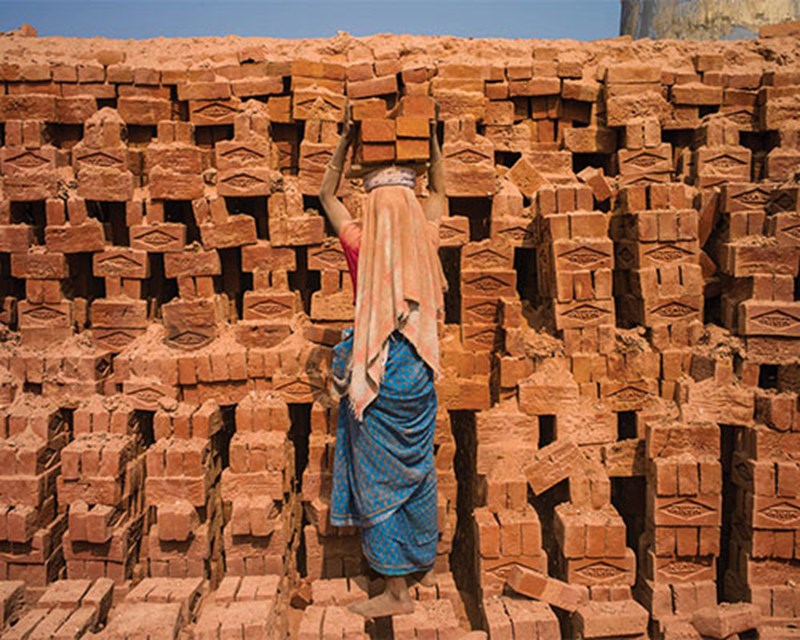

Women, on average across the world, are paid 24 per cent less than men. The women in those jobs are not 24 per cent less able, less experienced or less qualified. They are just 100 per cent less male. Pay inequality based on gender persists everywhere, across countries, regions and occupations, and it matters.

It matters because it is an evident injustice and because it condemns millions of women and their families to lives of entrenched poverty. It is a global, systemic problem that needs concerted attention and action to change the way that we value and support women’s work.

Race and ethnicity compounds the disparity. Though data is scarce in developing countries, in the US, for example, African American women earn only $0.60, Native American women $0.59 and Latinas $0.55 for every $1 that white men earn.

The gender pay gap has obvious immediate repercussions but also directly relates to longer-term impacts such as women’s credit-worthiness, savings, social security benefits and retirement income. Globally, some 200 million women in old age are living without any regular income from an old age or survivor’s pension, despite having been in the workforce in earlier life.

Where every dollar counts, pay inequality can be enough to plunge families below the breadline. Insufficient income reinforces the poverty cycle, limits opportunity and entrenches disadvantage; a sufficient income well spent on education, nutrition and health potentially moves a generation out of poverty.