Philanthropists are, on the whole, goodhearted people. But if they respond only to their heart, they are not likely to be good philanthropists. They are not likely to do the most good they can, and when people with the ability to do a great deal of good fail to do nearly as much as they can, they are not good at philanthropy.

There are many possible examples of ineffective altruism. Giving to the arts is, I think, one very large category of philanthropy that achieves relatively little good. But even within the broad category of improving the lives of people living in poverty, much giving is less effective than it could be.

Many American philanthropists focus on helping the poor in their own community. The United States has more gaps in its welfare net than most affluent countries, but even so, there are very few people in the US who are genuinely poor by global standards.

People who are poor in the US still have safe drinking water, free education for their children, free health care, and access to food stamps. The food stamps alone are worth more than $4 a day, double the income of the 700 million people who live below the World Bank’s extreme poverty line, which represents the purchasing power equivalent of about $2 today.

The fact that people in poor countries earn so much less than people in affluent countries makes a huge difference in our ability to help them. In the US, a family of four will be below the poverty line if the total family annual earnings are below $24,300. Suppose you give $1,000 to a family living on $20,000: that isn’t going to make a dramatic difference to their lives.

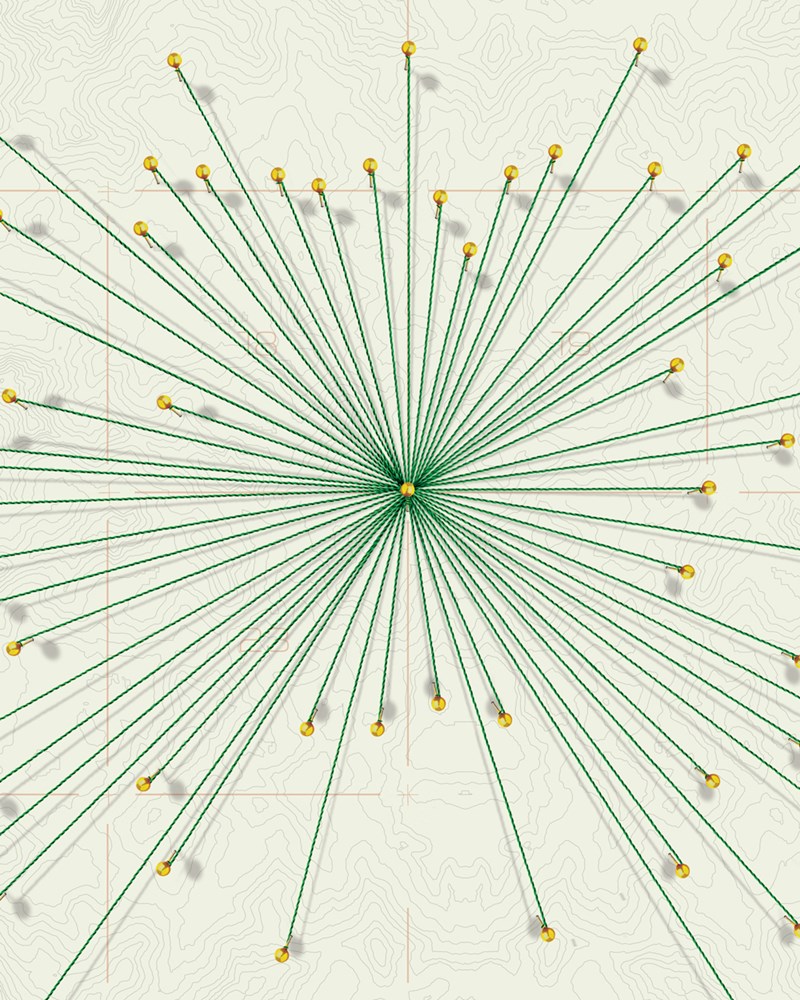

Now think of a family of four living below the World Bank’s extreme poverty line. We know what impact an additional $1,000 can do for them, because a charity called GiveDirectly finds very poor families in East Africa and gives them this sum of money. Independent researchers have tracked what these families do with their – non-repeatable – windfall.

The single most common use of the money is to replace a leaky thatched roof with a tin roof. Now when it rains heavily, the family – and their precious stores of grain – stay dry. They also save the cost of periodically replacing the thatch. And they may have enough left over to buy some chickens or start a small business.

Of course, not all families are so prudent. Some of them will just eat better for a year. Even when that happens, the money is likely to do much more good than if it were donated to a family that is poor only by the standards of an affluent country.

Even if you do decide to support a project in a developing country, however, it is important to check the evidence that what you are doing is a cost-effective way of making a difference.

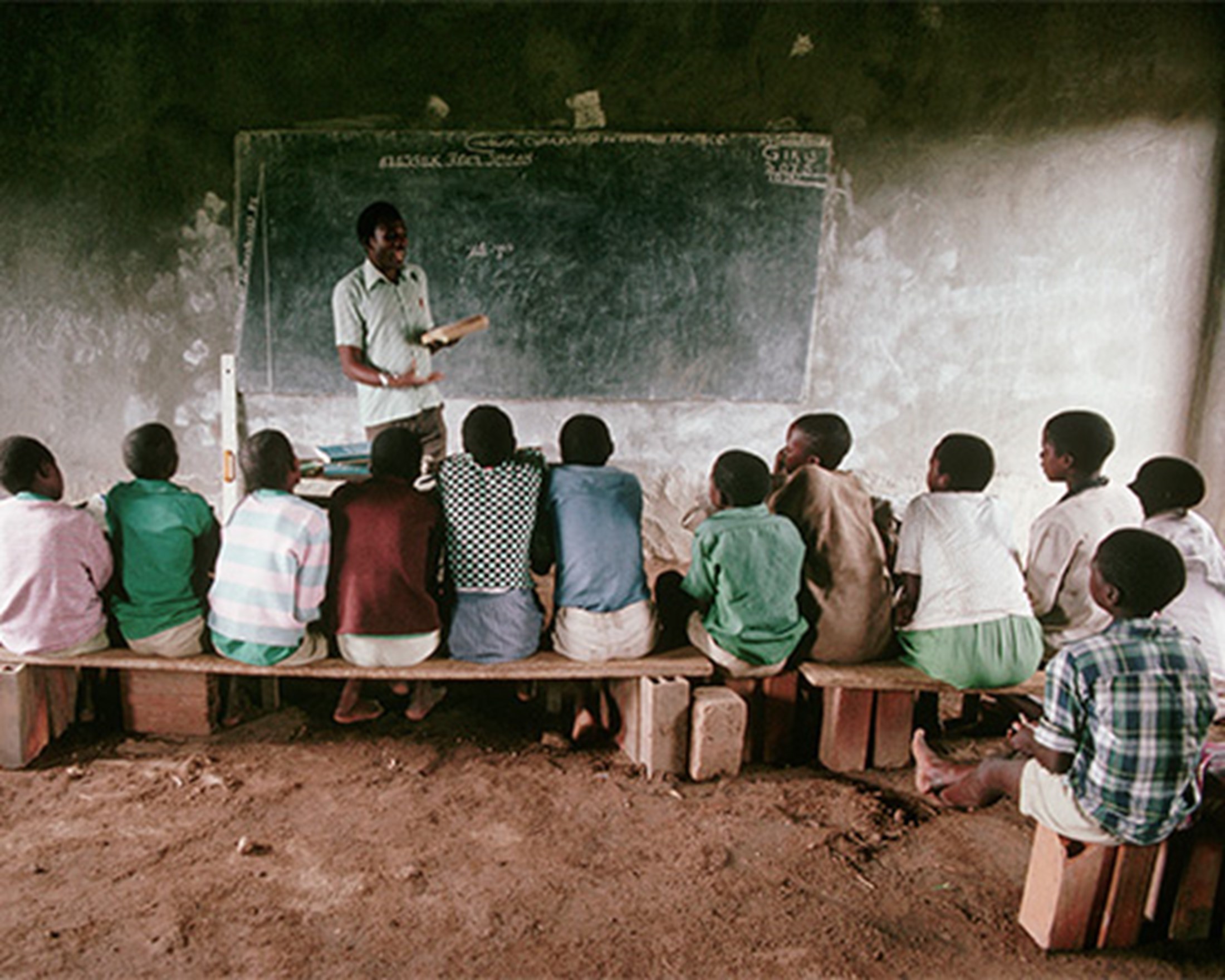

Suppose, for instance, you have learned that in East Africa, children – especially girls – often leave school before they have completed their education. If they stayed at school longer, they would have better opportunities in life, so you want to find a way of encouraging them to stay longer.

Charities have tried the following strategies to achieve this: cash transfers for girls; conditional on school attendance; and unconditional cash transfers for girls. Merit scholarships for girls; free primary school uniforms; and even the deworming of primary school children (that is, treating intestinal parasites). Some charities provide information to parents about the increased wages of those who stay at school.

Without proper testing, it would be impossible to know which of these strategies does the most good.

The Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) at Massachusetts Institute of Technology studied them and found that every $100 spent on providing information to parents about the increased wages of those who stay at school results in 20.7 additional years spent at school.

Deworming also appears to be highly cost-effective, leading to 13.9 additional years spent at school per $100 spent, although the results of one major study in this field have been challenged.

The other four interventions turn out to give much poorer value per dollar spent. None of them gains even one additional year at school per $100 spent.

The cash transfers are particularly poor value. Whether they are conditional or unconditional doesn’t make much difference; they each gain less than one- tenth of an additional year per $100. So, the most effective method results in more than 200 times the benefits of the two least effective methods. To put it another way: for every $100 spent on one of the least-effective methods, $99.50 is wasted.

If you bought a dishwasher, and then learned that you had paid 200 times as much as your neighbour paid for a machine that does just as good a job as yours, you’d feel really stupid. That isn’t likely to happen, because the company that made the high-priced dishwasher would soon be out of business.

But charities that cost 200 times as much to keep a child in school for a year stay in business, because their donors do not demand solid evidence of the effectiveness of their programmes.

Effective altruism is trying to change this by encouraging people to give with their head as well as their heart. Among the general public, most people who give to charity do no research at all on the charity to which they give. Often their donation is the result of an emotional response to an image, perhaps of a child in need of help.

It’s good that people have such impulses, but in a complex world with great differences in wealth, it’s not enough. Many philanthropists already realise that, but there are still many who do not.

Only a decade ago, it was very difficult to get good information on the impact that a charity gets out of each dollar it receives. Today, there are nonprofits such as The Life You Can Save, GiveWell, and Open Philanthropy, where you can find more information on which charities and causes have been examined and found to be highly effective.

This kind of evaluation is not easy or cheap to carry out. But it is far less expensive than giving money, year after year, without ever knowing whether you are doing the most good you can. - PA

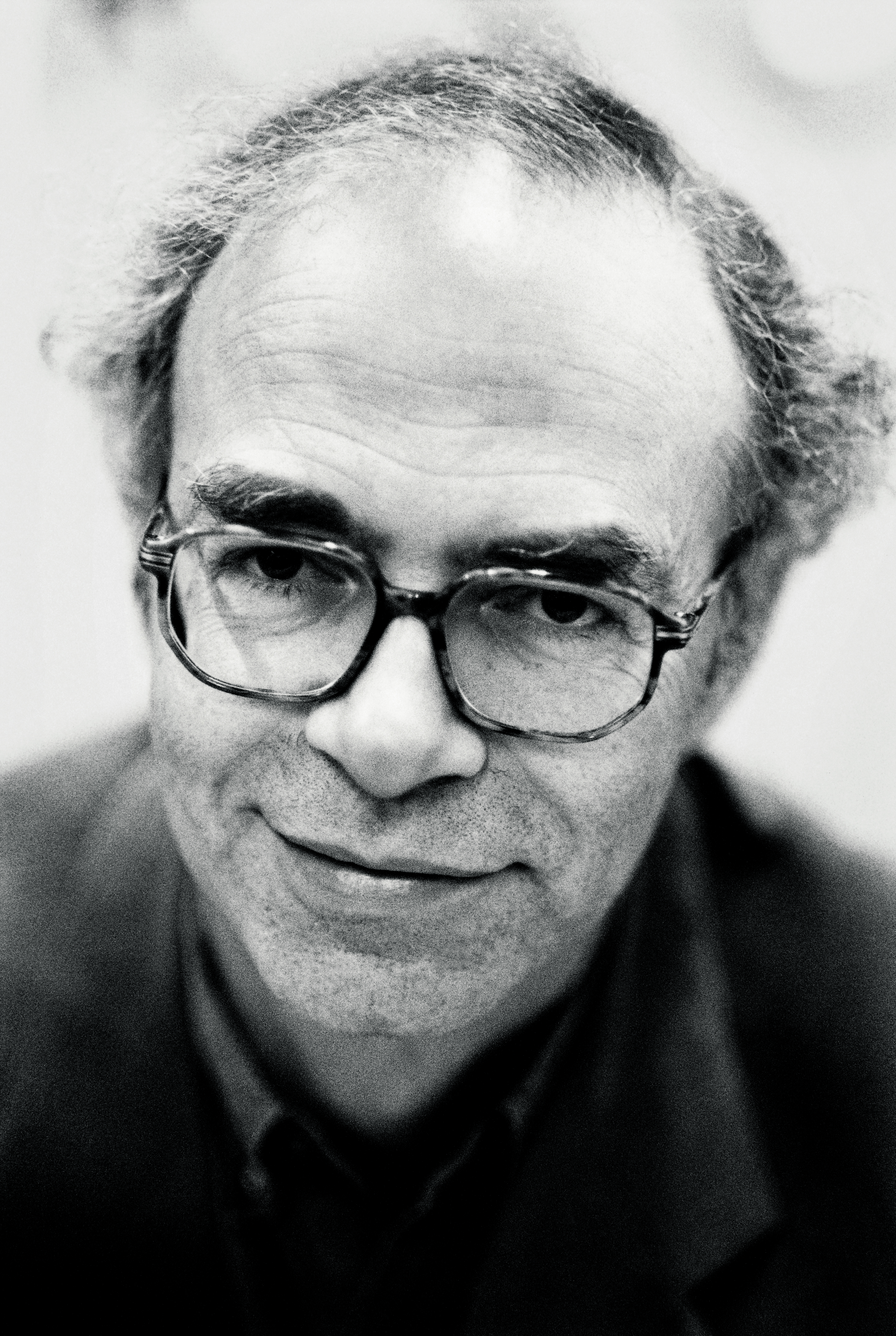

About the writer

Australian-born Peter Singer is a professor of bioethics at Princeton University. His books include: The Life You Can Save, The Most Good You Can Do, and Why Vegan?

Named as the winner of the 2021 Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, Singer pledged to give half of the $1m prize to The Life You Can Save, a nonprofit he co-founded to highlight good giving and inform donors.