Each day, hundreds of refugee children crowd the rooms of the Chalhoub-Jusoor Learning Centre in Lebanon’s impoverished Bekaa valley for lessons in reading, writing and maths. More than 3,600 five to 14-year-olds have passed through the centre’s doors; mostly Syrian, and many having missed years of formal education. Classes are taught by a team of 20 teachers from Jusoor, a nonprofit founded by Syrians, and there is also a homework club for students falling behind in core subjects, and a summer camp. With 69 per cent of Syrian refugee families in Lebanon living below the breadline, and 40 per cent of Syrian children not in school, the centre is an effort to prevent the students’ futures also being lost to war.

It’s a project funded wholly by Chalhoub Group, a Dubai-based luxury retail business with operations in 14 countries and a keen focus on sustainability. With a philanthropic interest in education, the environment and humanitarian issues, carried out through a range of community initiatives, Chalhoub is reflective of a small but growing number of GCC family-owned businesses working to apply a strategic lens to their giving.

“Our approach is led by the family but very much embedded in the needs of the region,” explains Florence Bulte, head of sustainable engagement at Chalhoub. “What matters for us is to have a tangible and positive impact on the people we are seeking to reach.”

Family businesses are the quiet powerhouses of Gulf philanthropy. Representing some 90 per cent of the private sector economy, they are among the region’s largest donors to social and charitable causes. No precise data exists for their giving, but consultancy firm Strategy& estimates the GCC’s top 100 family firms alone wield at least $7bn in annual philanthropic capital.

This generosity is in some cases mandated by governments – in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, for example, locally owned firms pay an annual Islamic tax calculated on their net worth or profits – but chiefly fuelled by cultural and religious traditions. And as the region’s wealth expands – the Middle East’s ultra-rich population is predicted to swell by almost a fifth by 2024 – likely, so too, will giving.

Used well, this money could help unravel some of the region’s knottiest social and economic problems – particularly as government spending ebbs away, says Fadi Adra, partner at Strategy&’s Middle East office. But doing so would mean turning a culture of often diffuse and unfocused philanthropy on its head.

“The challenge is that the focus among family businesses is often still on giving money away rather than on generating impact,” he notes. “We can talk about inputs, but rarely about outcomes."

Several factors are to blame. One is the complex web of red tape that governs the set-up of private foundations in the region and dissuades families from formalising their giving. As a result, many still tilt towards ad-hoc donations and grantmaking rather than planned giving, making it difficult to gauge the impact of their funding. Another is discretion, long a characteristic of giving in the region, and one heightened among family businesses that are, by definition, private. More than half of the GCC’s largest players don’t disclose their philanthropy, according to Strategy&, a finding that resonates with Khalid Al Zayani, honorary chairman of Bahrain-based Al Zayani Investments.

“It’s not like the west. Company giving isn’t tax-deductible, we aren’t obliged to do it and we don’t necessarily feel the need to publicise it,” he explains. “The Gulf is a small community, and each family has its own style and way of giving.”

This opacity can make it difficult to highlight good philanthropic practices, or to spot opportunities for learning and collaboration, says Yasmine Omari, executive director of Pearl Initiative, a nonprofit that promotes corporate accountability and transparency among GCC companies.

“Openness helps to streamline giving. We already see that among some small communities of family offices and businesses. They all give to one cause, purpose in mind, and they benefit from the increased impact and cost efficiencies that go along with that,” she says.

“The focus among family businesses is often still on giving money away rather than on generating impact.”

Fadi Adra, partner, Strategy& Middle East.

A third factor is disillusionment with the giving vehicles available. The GCC is short on innovative tools such as impact investing, social bonds or outcome-focused funds, partly because it lacks the philanthropic ecosystem needed to create them. This means family firms tend to fall back on grantmaking to local nonprofits or charitable handouts – options that have the benefit of being both quick and sharia-compliant.

A 2018 report by Pearl Initiative, which surveyed 31 Gulf corporations, foundations and family firms, found 84 per cent of their giving went to local nonprofit and philanthropic organisations. Just over a quarter was in the form of cash donations.

“The alternative to grantmaking is social investing: defining a cause, understanding the root problem, and investing for long-term results,” says Adra, from Strategy&. “These vehicles aren’t readily available in the local market yet. The landscape isn’t mature enough.”

This creates a tricky loop. Social investment tools have impact measurement baked into their model. Local charities are typically less sophisticated and – in a region where few donors demand outcome metrics – feel little pressure to reform. Bulte at Chalhoub says the group has at times struggled to find nonprofits capable of sharing the level of data it needs for funding applications, and it has sympathy with family businesses opting for an easier path.

“Impactful engagement takes a lot of time and effort. If you as a family business don’t have a proper structure in place you may have to be lenient in how you donate, because the alternative is just too time-consuming,” she says.

The balance may be beginning to tip, weighed by two trends. The first is the growing realisation by Gulf governments that social issues are best tackled collaboratively. In countries including the UAE and Saudi Arabia, where stringent laws keep the nonprofit industry in check, groundwork is being laid for a bigger and more effective social sector.

Moves in the emirates include a national CSR law to document, direct and incentivise corporate giving, and a state-led push for more and better nonprofit initiatives. One eye-catching example is Abu Dhabi’s agency for social impact, known as Ma’an. In the year since its launch it has unveiled an investment fund, an incubator for nonprofits and social enterprises, and plans to use its social impact bonds to finance public services.

Saudi’s tactics to rally the sector include a promise by the government to find and scale effective nonprofits, and a pledge to smooth the path for wealthy families eager to set up their own outfits. More explicitly, the kingdom’s growth plans require more than a third of nonprofits to demonstrate “measurable and deep social impact” by 2030 – a big ask when an estimated half of key employees in the sector don’t hold the necessary skills for their role. If successful, family businesses will have a much-improved marketplace of causes to pick from.

“The trajectory is positive. Governments are becoming more open and collaborative: they want to enable rather than police [the industry],” says Adra. “By formalising the third sector, they can help focus efforts and increase the return on invested dollars.”

The second trend stems from family groups themselves. Experts say a growing share are choosing to swim against the tide and make philanthropy a public part of their mission, in alignment with their family values and culture.

“They recognise this is a venture in itself. Just as they have to manage their investments and their portfolio and the family business, they have to manage their philanthropic giving,” says Pearl Initiative’s Omari.

Among these high-profile outliers is Saudi’s Abdul Latif Jameel Group, whose social enterprise arm Community Jameel works to solve headline issues ranging from unemployment, to poverty and hunger. Its Bab Rizq Jameel programme, which focuses on propelling youth in Saudi, Egypt and Morocco into jobs, reports to have secured 900,000 employment opportunities since 2003.

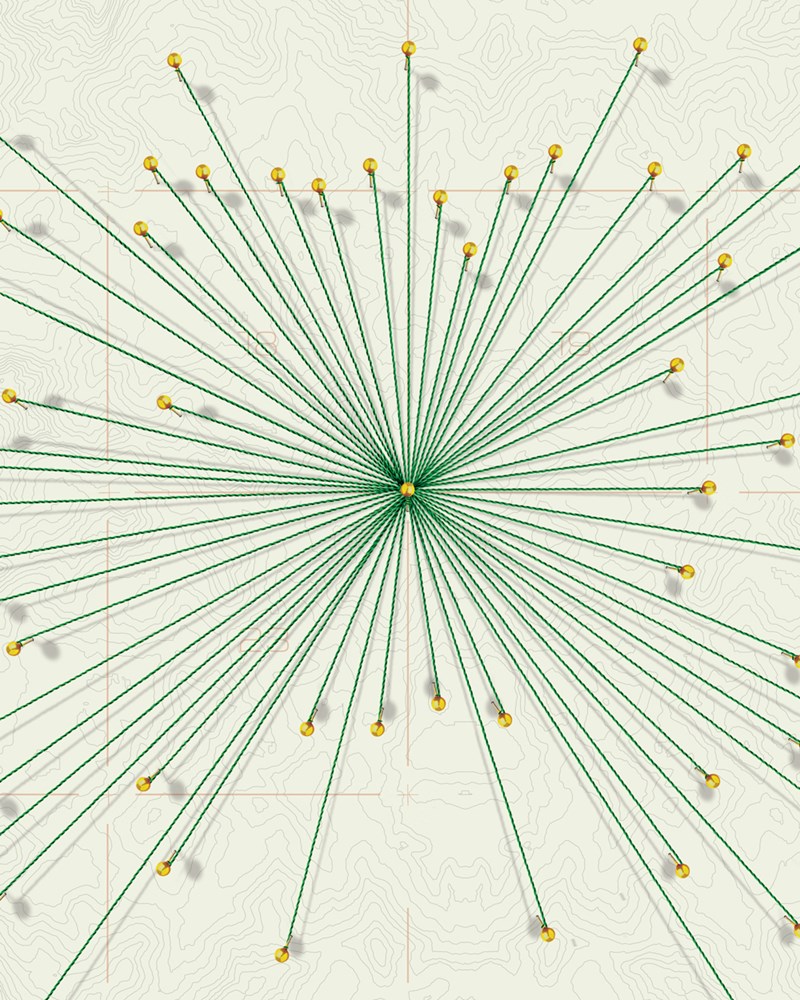

The family’s partnership with MIT created the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab – or J-PAL for short – a global research centre that uses data to identify poverty-fighting policies that work, in a bid to effect change for billions of people around the world. Community Jameel has also funded the Jameel Institute at Imperial College London (J-IDEA), which has been at forefront of the global response to Covid-19, using data modelling and computer science to inform policymaking on how to control the pandemic.

The UAE’s Al Ghurair family is also helping to put strategic philanthropy on the regional map. At $1.1bn, the family’s education foundation is one of the largest privately-funded initiatives of its kind, offering scholarships, skills training and other opportunities to bright and underserved Arab youth. Its chairman Abdulaziz Al Ghurair has also spoken openly about the need for Gulf philanthropists to collaborate, and to think strategically about their giving outcomes.

“For many, philanthropy is part of the family DNA and we take it seriously,” agrees Abdulrahman Al Turjuman, acting head of CSR at Sedco Holding, a wealth management organisation in Jeddah operated by the Bin Mahfouz family. The family operates a foundation, named after late patriarch Salem Bin Mahfouz, while Sedco runs a free nationwide programme to tackle financial illiteracy and offers pro bono consulting to nonprofits, entrepreneurs and other groups.

“We focus on issues that impact the community and are also relevant to our business,” explains Al Turjuman. “Our goal is to be impactful and sustainable at the same time.”

“While the current generation has focused largely on philanthropy, the next is opening its eyes to alternative models of social improvement.”

Rebecca Gooch, director of research, Campden Wealth.

Also aiding the swing is the transition of wealth away from older family members and towards second or third generations, who are prepared to invest in new ways of doing good. With deep pockets, long time horizons and limited public scrutiny, family firms have the flexibility to experiment with novel tools. By way of reference, of the 360 family offices that took part in the latest annual Global Family Office Report by UBS and Campden Wealth, a quarter say they are active in impact investing. More than a third (37%) of family offices expect to increase their allocation over the next five years.

“The sustainability space is an important one to watch,” says Rebecca Gooch, Campden’s head of research. “While the current generation has focused largely on philanthropy, the next is opening its eyes to alternative models of social improvement.”

The increased willingness among family businesses to examine the impact of their philanthropy, combined with a fresh drive from GCC governments to reform the nonprofit sector, suggests corporate giving will become an increasingly active force for good. With billions of dollars in wealth expected to pass to younger family members over the coming years, businesses that make philanthropy a cornerstone of their mission could also reap benefits in terms of their own longevity.

“I always say to family offices that your income and profits come from the community,” says Khalid Al Qoud, a Bahraini entrepreneur and consultant who advises businesses in the Middle East on social responsibility. “If you have not strategically given back in a way that positively impacts them, you won’t be here within the next, or at a maximum, the fourth generation.” — PA