Of the 1 billion people worldwide existing in extreme penury, 40 per cent live in the Muslim world. For these stricken households, life may be looking up. Last June, to little fuss, Bill Gates, cofounder of the world’s wealthiest private foundation, and the Jeddah-based Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) unveiled a $2.5bn fund aimed at hoisting some 400 million people over the poverty line, and out of destitution.

“We have the expertise, and the IsBD knows how to get things done in the region,” Gates says of the partnership. “Those are really the things that count.”

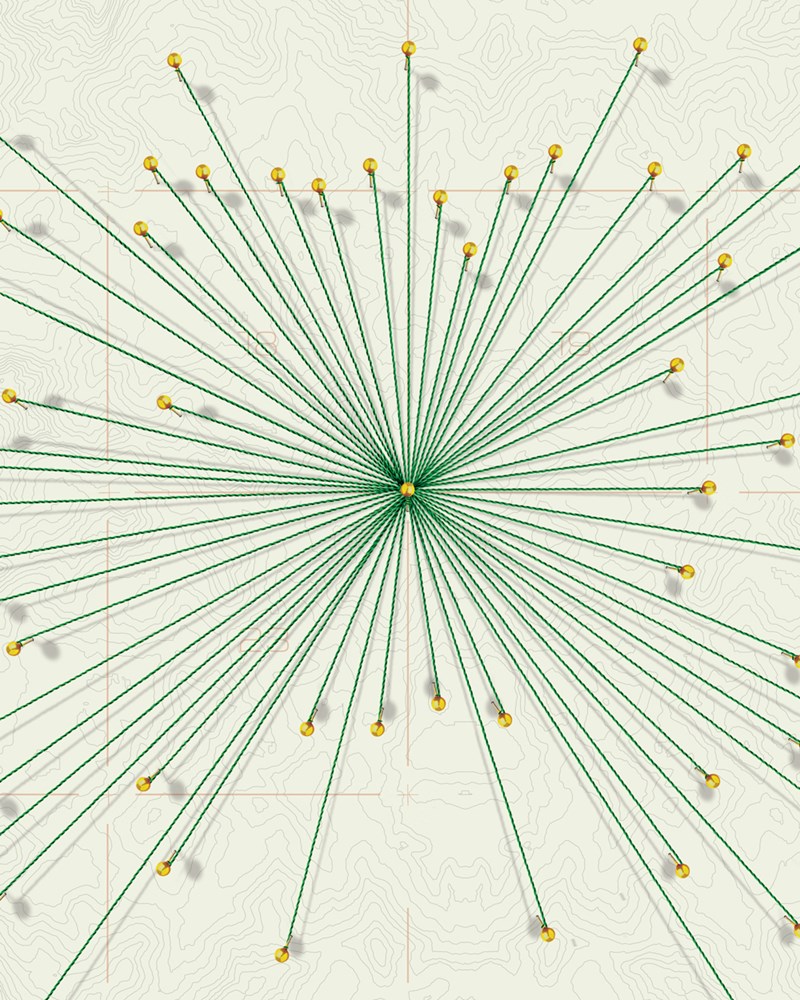

The plan hinges on cheap loans. Over five years, the IsDB will disburse $2bn to projects in health, agriculture and infrastructure in the 30 poorest Muslim countries. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is raising $500m in grants to trim the interest payments on these loans and put them in reach of the most impoverished states, chipping in $100m itself.

The IsBD-backed Islamic Solidarity Fund for Development has pitched in a further $100m, while Qatar in April put in $50m. Gates, beating the drum for further donors, hailed it as “an incredible opportunity for anyone who cares about driving social change”.

“It’s a pretty significant fund,” he says today. “I’m hopeful.”

At 60, Gates is still seeking out new frontiers. A Harvard dropout, he made his name as a tech titan, building the world’s first software fortune in the totemic Microsoft Corp. The company listed in 1986 and within a year, Gates, at 31, had become the world's youngest self-made billionaire.

He stepped down in 2008, one of the world’s richest men, to devote his time to the foundation he and his wife Melinda had launched eight years earlier.

Today, the Gates Foundation is the world’s biggest private philanthropy, doling out close to $4bn a year to causes as diverse as education, sanitation and women’s health, in the pursuit of ending poverty and disease. By all measures, Gates is the most influential philanthropist on the planet.