In June 2013, Regina Catrambone was aboard a chartered yacht with her husband Christopher and daughter Maria Luisa for a sailing trip to the coast of Tunisia. As the yacht motored out from the harbour in Lampedusa, a tiny, picturesque island off the Sicilian coast, the Italian entrepreneur spotted an object bobbing gently on the water.

It was a winter jacket, a peculiar sight in the warm summer sun, and she asked their captain about it. He told her it had likely come from one of the thousands of migrants who’d attempted to cross to Italy from Libya, crammed into flimsy inflatable dinghies or fishing boats – one who had drowned in the process.

“Seeing that jacket was for us a tangible sign of how people were dying at Europe’s doorstep, in the same waters we were sailing in,” says Regina, who runs the multinational Tangiers Group with her husband, providing insurance and other services in conflict zones. “We realised that we were sailing over a grave.”

When Pope Francis weeks later inveighed against the “globalisation of indifference”, in his first visit outside the Vatican, the Catrambones took note. And by October, when more than 300 refugees – many from Somalia and Eritrea – drowned within sight of Lampedusa when their boat caught fire and sank, they’d taken action.

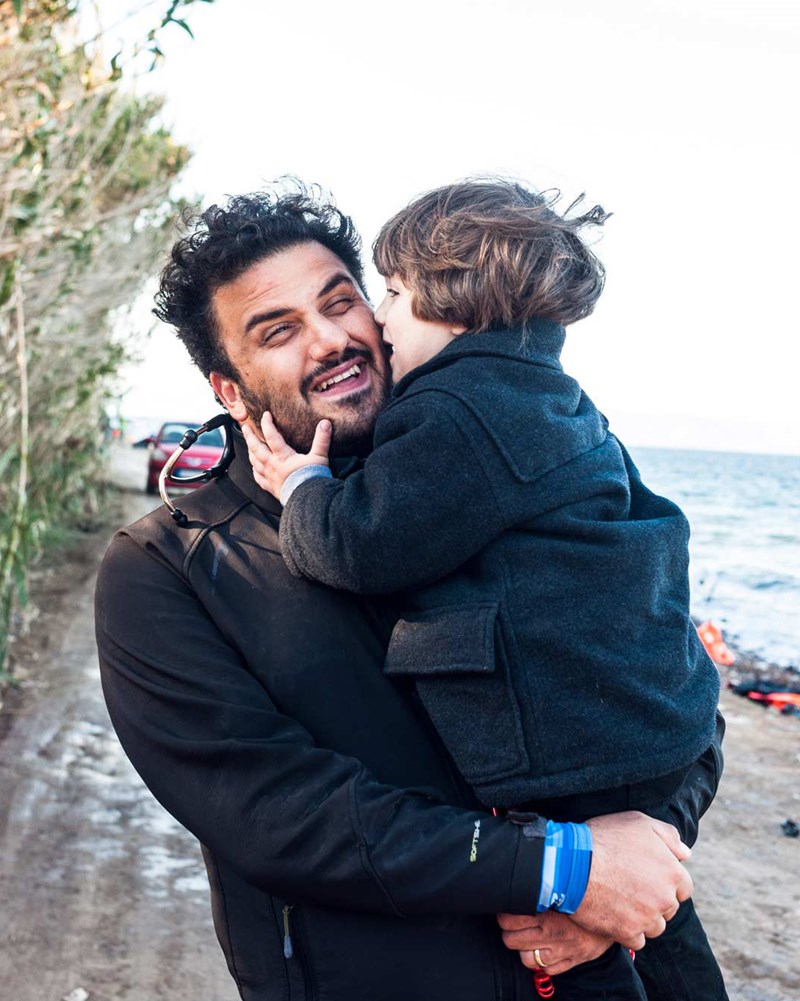

The Migrant Offshore Aid Station, or MOAS, completed its first mission in late August 2014: a 90-day stint, funded by the Catrambones, in which it helped to rescue 3,104 migrants. Its boat, the Phoenix, is a 130ft ex-fishing trawler kitted out with drones, a helipad, a medical clinic, speedboats and inflatables to prop up listing vessels.

Now marking its third birthday, MOAS has come to the aid of more than 40,000 women,children and men – ranging in age from two days, to 92 years – both in the Mediterranean and, more recently, in South East Asia. The motto behind the first search-and-rescue NGO is simple: nobody deserves to die at sea.

“You will never stop migration; no one can. People will always be willing to make the crossing,” says Regina. “But what we can do is try to help them. We have a responsibility to do that.”