A one-hour meeting was all it took for Jim Estill to get a plan to bring 50 Syrian refugee families to Canada off the ground, and into play. The CEO of multimillion-dollar home appliance firm Danby rounded up aid and religious organisations in his home city of Guelph, zipped through a brief PowerPoint presentation, and asked them to join the cause.

“And they said they would,” he says easily, “so that was that.”

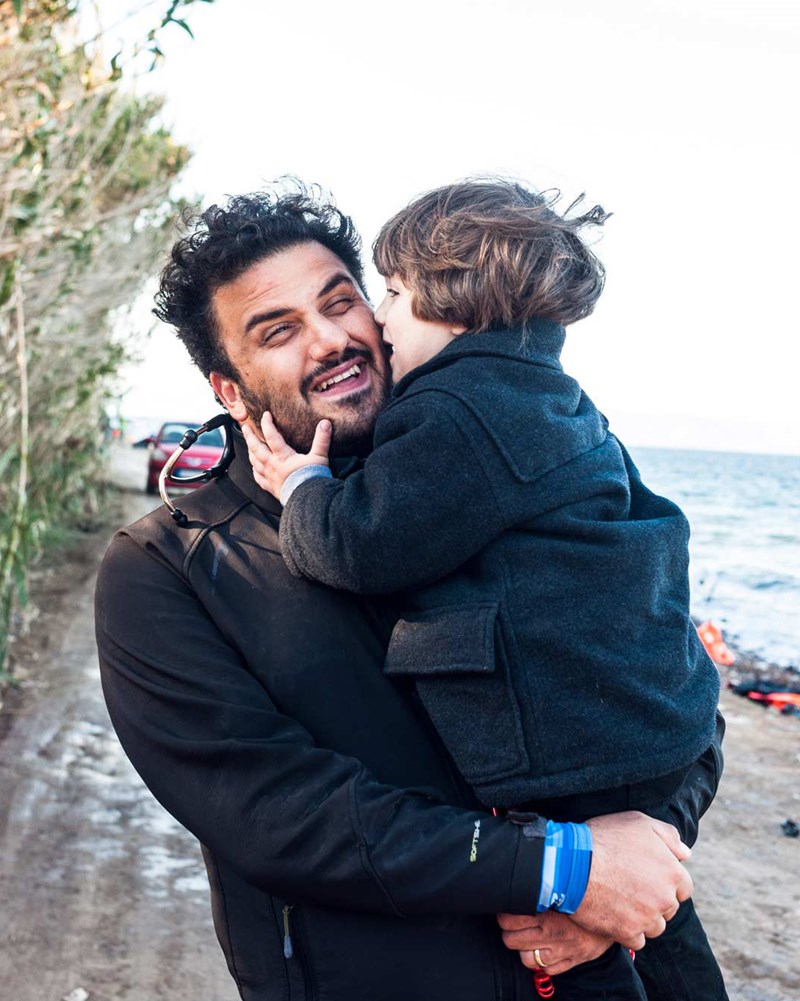

Estill is a doer. A serial entrepreneur, he has built companies and a career on the maxim that even indecision is a decision and that – when in doubt – you should do the right thing. In the summer of 2015, as the count of Syrians fleeing their country reached 4 million and the toll of those dying at Europe’s shores rose, Estill felt the need to act.

Over the next few days he appraised local rents, calculated a food budget, and checked his sums against the government’s welfare rates. Based on his estimates, he worked out that it would cost him C$30,000 (about $23,000) a year to fund a family of five in Guelph, a small city about 93km outside Toronto.

By putting up a budget of $1.5m, he could afford to support about 50 Syrian families for a year under Canada’s private sponsorship programme.

That was the plan he pitched to the Muslim Society of Guelph, the Salvation Army, and a clutch of local churches and synagogues, to ask for their help in fostering a citywide volunteer network to help settle the families into new lives.

“I didn’t think it was a big deal,” Estill says today. “As an entrepreneur, I always say ‘I do something’ – it’s not in my DNA to look the other way. Bringing in 250 people seemed proportional in a city of 130,000, and I thought that if every Canadian citizen did their part, we’d be able to empty the lake with a bunch of thimbles.”

Much of the world has reacted to the global refugee crisis with a mix of hesitancy and hostility. In Canada, citizens have rallied to welcome them. Private sponsorship began in the country in 1978, in the aftermath of the Vietnam war, and allows private citizens to bring in and settle refugees as long as they commit to shouldering their expenses for the first year.

More than 250,000 refugees have come to Canada so far under the scheme, including thousands of Syrians since the outbreak of war in 2011. As a child, Estill’s own family billeted two young men who had fled Uganda, though he mainly recalls annoyance at being moved out of his bedroom to accommodate them. “I was eight,” he laughs. “But they became fast friends.”

Estill’s scheme was ambitious. Though staffed by volunteers – and buoyed by donations - it would run like a business: a full-scale operation offering refugees everything from English-language classes, to furniture, housing, and job training.

Each family would be matched with Arabic and English-speaking mentors, to aid in tasks ranging from finding a doctor, to setting up a bank account and grocery shopping. For the first month to six weeks, newcomers would be billeted with a host family.

The scheme’s success would be decided by a clear outcome, Estill decided: 50 families who work, pay taxes, buy groceries, speak English and have a degree of integration. “The aim has to be independence,” he says. “Success is not 50 families on welfare. It’s not people who are ghettoised. You don’t help anyone by just writing cheques.”

Getting the city on board proved easy. Within weeks “we had people coming out of the woodwork,” says Estill, as more than 800 volunteers scrambled to join the cause. They were spun off into teams – healthcare, finance, education, jobs, transportation, mentorship – each led by a director, and charged with helping newcomers navigate one aspect of their new lives.

In town, a large, rented warehouse strained at the seams with donations of furniture, kitchen appliances, bedding, dishes and clothes.

“I tell my friends, if you can run a business with 800 employees, you can run an organisation with 800 volunteers,” Estill says briskly. “This was no different. It’s just organising and executing on a bigger scale.”

Harder was choosing who would come. In November 2015, a story about Estill’s plan appeared in a local paper. Within days, it had been translated into Arabic and shared across the Middle East, lighting up news feeds from Beirut to Cairo.

At first, Estill received just a trickle of messages from refugees pleading for his help. But as the weeks passed, the emails stretched into the thousands, as families in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and even Syria begged to come to Canada. Estill read them all.

“It’s terrible, because you are playing with their lives,” he says quietly. “How do you choose who to help, when you can’t help them all?”