“There are not enough resources to tackle all the world’s problems. You have to make the biggest impact with what is available through innovation and doing things differently,” explains James Chen, who likes to use the term “moonshot philanthropy” to describe his approach to giving – and the risks involved.

“Without the tangible possibility of failure, and without embracing the risk of testing unconventional out-of-the-box ideas,” Chen adds, “we would never be able to shift the paradigm on the complex issues we each seek out to resolve.”

Philanthropists often like to talk about taking risks and innovating in order to scale solutions. And Chen, through his commitment to improving eye health in Africa, has really walked that talk.

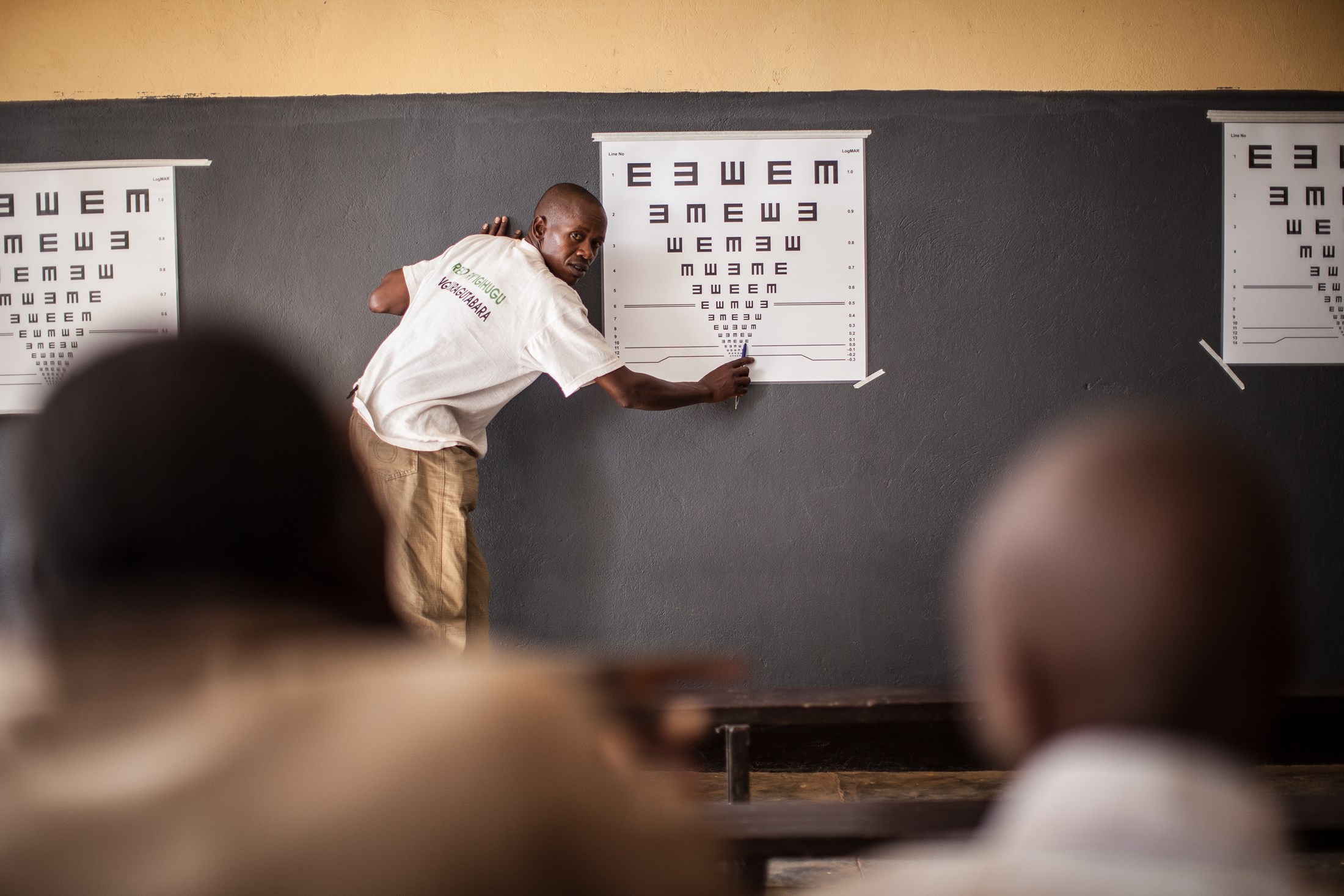

His pilot scheme to train healthcare workers in Rwanda, delivered in parallel with the distribution of low-cost glasses, grew to become part of a nationalised system that was adopted regionally, sparking a global campaign that culminated last year in a UN resolution. It doesn't get much more catalytic than that.

Chen is the definition of a global citizen. He was born in Asia (Hong Kong) and raised in Africa (Nigeria) where his father worked, and studied in the United States, doing a Bachelor's in behavioural science at the University of Chicago.

Today, he lives between the US, the UK, and Hong Kong, chairing the family’s Wahum Group Holdings, and running Legacy Advisors Ltd, a family office he set up to manage Wahum’s profits, and in 2019, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Bath.

It’s a long way from the Shanghai factory floor where his grandfather, Chen Zao Men, started out as an enamelware apprentice aged just 16. But from those humble beginnings, the Chen family grew to become extremely wealthy, first through the factories Chen Zao Men opened in China and Hong Kong, and then thanks to expansion into the newly independent West African countries of Ghana, Nigeria, and Cote d’Ivoire, led by his son, Robert.

Over his lifetime, Chen Zao Men made regular philanthropic donations to the communities in which the family worked, supporting schools, hospitals, and other public works initiatives.

Robert was also a keen donor and in October 2003, with his wife, daughter, and son, he established the Chen Yet-Sen Family Foundation with a view to spend his retirement stewarding a strategic giving programme.