Born and raised in a small college town in the American Midwest, Steve Sosebee knew little about the Middle East growing up, and says he had never met an Arab until he started studying political science at Kent State University. Following a three-week visit to the West Bank and Gaza during his junior year, Sosebee returned to Palestine as a graduate in 1989, this time as a freelance journalist on a mission to write about and raise awareness of the plight of those caught up in the violence of the First Intifada (uprising).

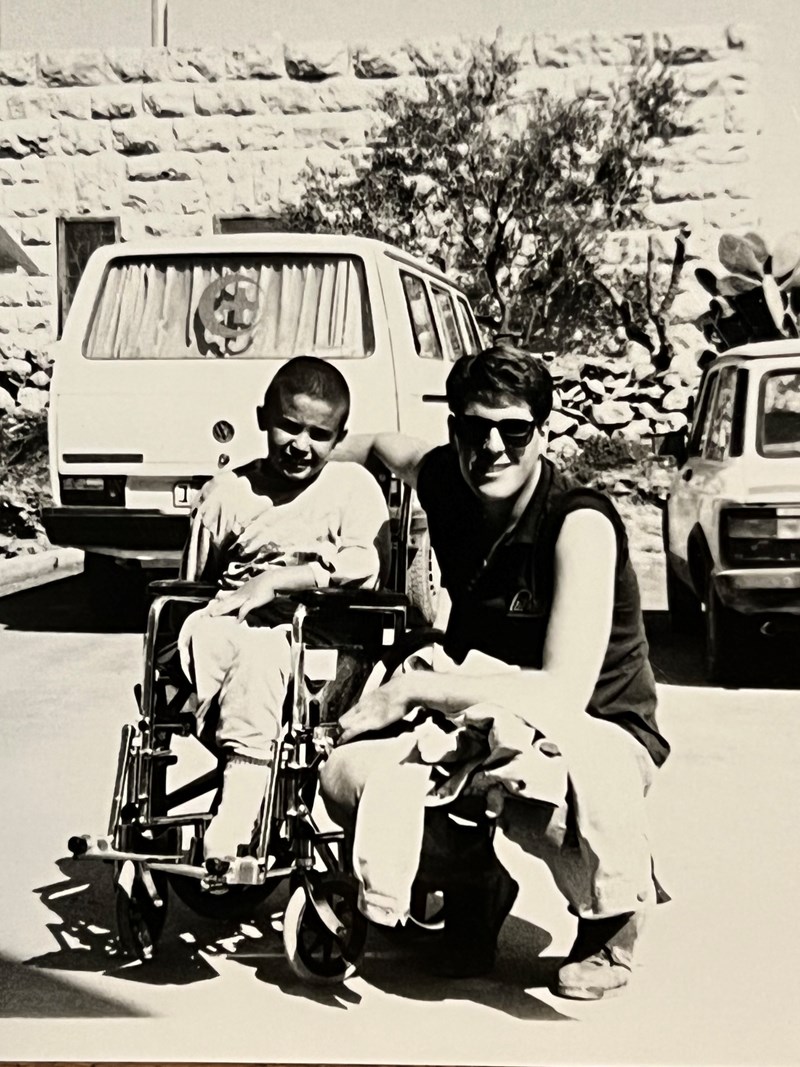

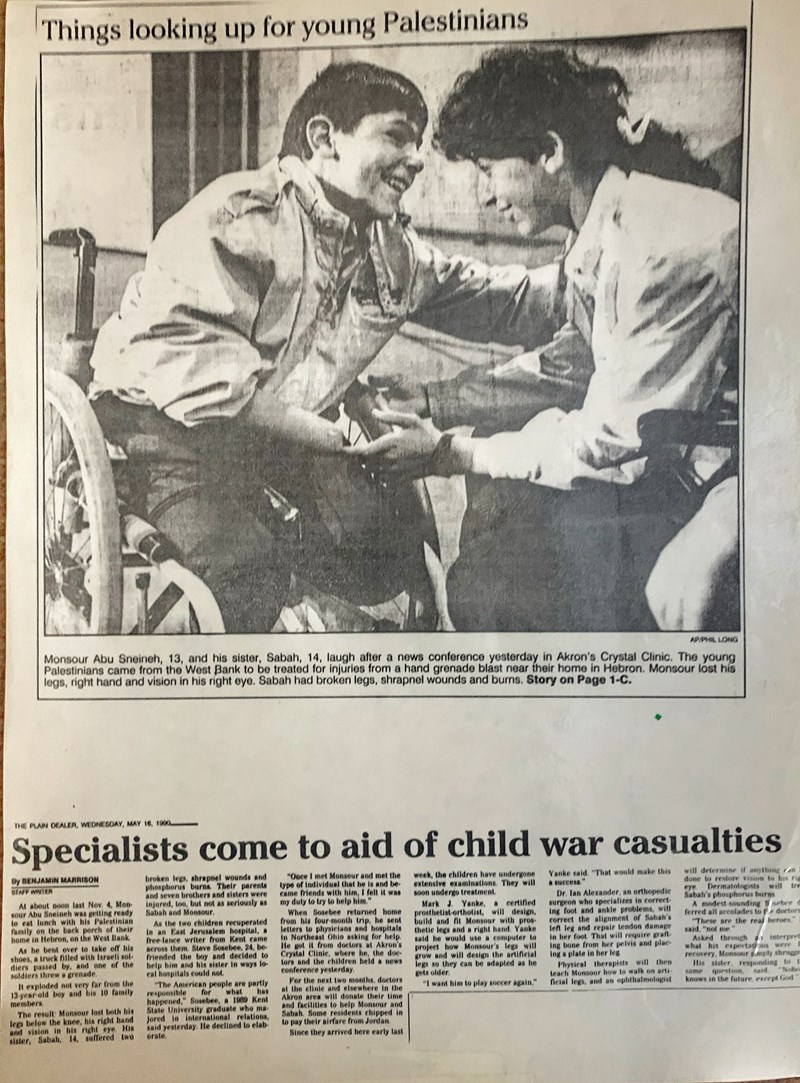

But when he met 10-year-old Mansour - who lost both legs and a hand in an Israeli bomb blast near his home in Hebron - everything changed.

A news report wouldn’t be enough, realised Sosebee, who found himself steered onto a path that would change his life - and the lives of many others – and lead to the formation of the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund (PCRF), an award-winning humanitarian organisation supporting sick and injured children across the region.

“I saw this child in a wheelchair without legs and I couldn't just write a story about him and walk away,” Sosebee recalls. “I didn’t know what I was doing… but if I didn't do something, who was going to?”

Three decades later, PCRF is a multinational NGO with chapters in 25 countries. Sosebee, 58, is the president, but he has a CEO, Imad Nassreddin, an advisory board, a global staff of more than 60, and a huge pool of medical volunteers from the US, Canada, Japan, Egypt, France, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, and beyond.