Cracking the code

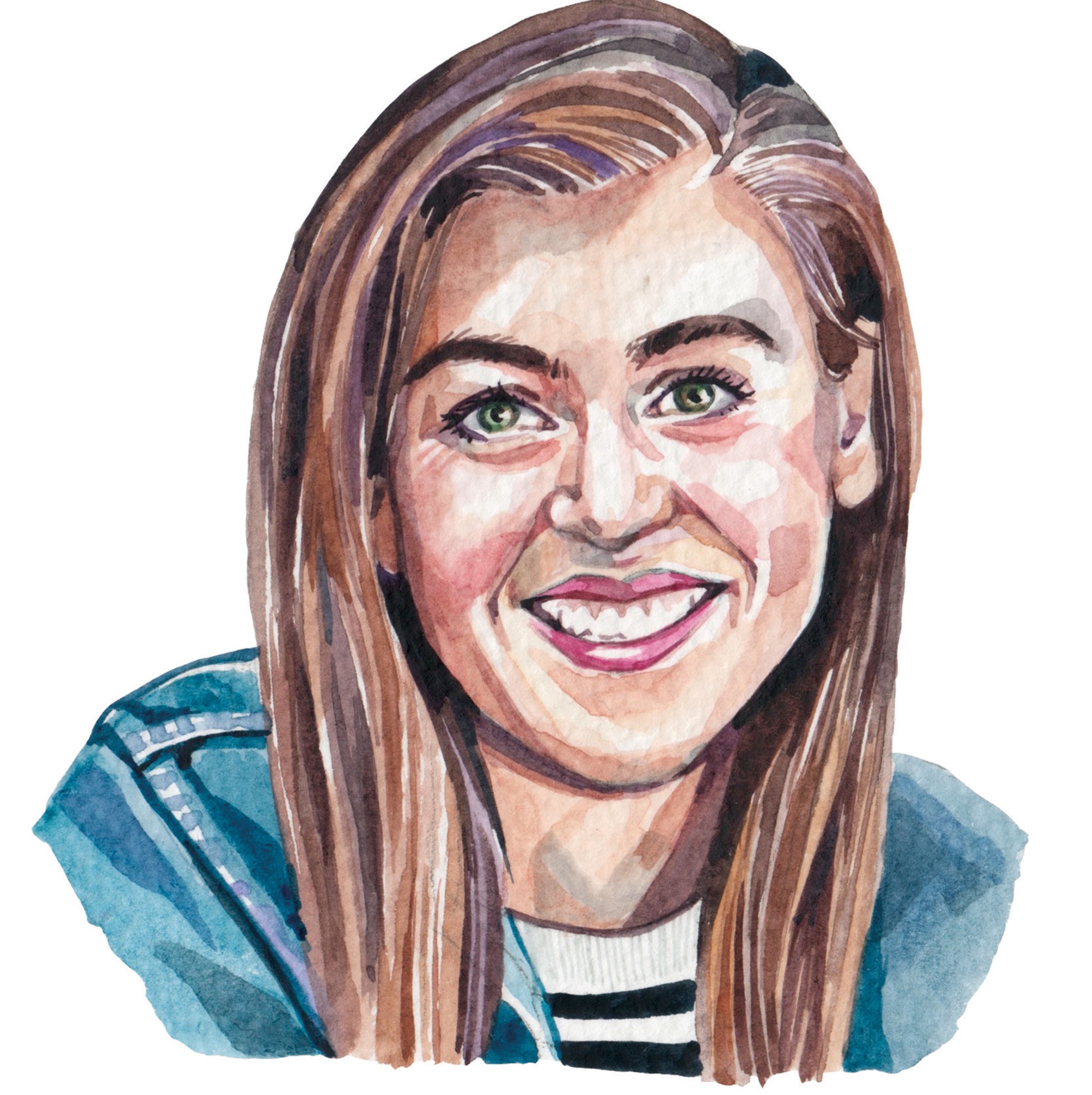

Alexandra Clare — Iraq

Alexandra Clare — Iraq

Iraq is a country more synonymous with conflict than coding. Long-standing economic woes exacerbated by the country’s three-year fight with Isis, have left Iraq heavily dependent on oil, grappling with rising poverty and with a youth unemployment rate of 40 per cent. One way of tackling this, according to Alexandra Clare, is by giving youth access to the digital economy, and equipping them with the technical skills they need to secure remote online work.

Clare is the co-founder of Re:Coded, a coding and startup training programme for conflict-affected youth in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. It was founded in New York in 2017, after Clare saw the scale of the Arab region’s unemployment problem.

“In 2014, during my travels to Iraq, I found that only three per cent of displaced youth had access to education,” she explains. Job opportunities were similarly scarce.

Clare previously co-launched a humanitarian innovation accelerator at New York University’s GovLab that helped teams develop solutions for people in disaster and conflict zones, dug further.

“I interviewed over 400 young people, asking what skills they wanted to learn,” she explains. When over 98 per cent responded with ‘technology’, “the ‘aha’ moment for Re:Coded was born.”

Clare joined forces with entrepreneur Marcello Bonatto, who had been working with conflict-affected youth in West Africa, to get Re:Coded off the ground. Since then, the nonprofit has taught coding to over 450 young people and children in Iraq, Turkey and Yemen, via a blended online and in-class curriculum.

Particularly vulnerable students are given a stipend to offset transport costs, and access to a laptop loan programme. Trainees also benefit from career advice and apprenticeship opportunities. For aspiring entrepreneurs, a tech startup academy offers skills training and mentorship.

Initial results, says Clare, have been encouraging. “Eighty-eight per cent of our students are now working as software developers, earning at least three times more than what they were earning before,” she explains.

Over 40 per cent of students are female.

As with Iraq, eight years of conflict in Syria and the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Yemen have led to millions in the region being displaced from their homes. With economies at a standstill, job opportunities are few and many work in the informal sector, where pay is low and exploitation high.

“This is particularly concerning for young people with a university degree and a dream of a better tomorrow,” says Clare. “Learning to code can allow youth to join the digital economy and avoid negative coping strategies.”

The internet acts as a lifeline to international marketplaces, allowing trainees to work as remote developers or start their own tech startups. They can also pitch work to regional markets, where Arabic-language content is in high demand. It’s a solution that could simultaneously help to tackle another growing need, says Clare.

“We’re also helping to fill the global technical skills shortage, something which is estimated to cost the global economy $8.5 trillion per annum in unrealised revenues.”

Re:Coded currently receives funding from agencies including the United Nations Development Programme, Western Union Foundation, Asfari Foundation and Google, who are keen to drive progress in the region through innovation.

Revenue from providing tech services also contributes a valuable boost. Last year, Re:Coded started a digital agency to create products for global organisations.

“The fees we charge for services not only provide an income for the talent coming out of our bootcamps,” says Clare, “but 50 per cent of the revenues we generate are reinvested back into our education model. This will ensure we can be financially sustainable in the long-term.”

Besides funding, finding technical experts to train participants is a major challenge. “We're in a good place to start scaling this model,” says Clare. “To do this, we want to invest heavily in our trainers’ programme to ensure we build local capacity.”

Re:Coded plans to expand to Egypt and Jordan and include blockchain and AI in its programme offerings.

“If we don’t invest in it now, we'll end up with more mass migration and greater income inequality,” she explains. “We believe our youth can become leaders in their communities. That is the most powerful multiplier effect.”

“Learning to code can help youth to join the digital economy, and avoid negative coping strategies.”

Fatima Nasser — Libya

Those at the sharp end of tough social and economic problems often have creative insights into how to solve them. So it is with Fatima Nasser, a 21-year-old Libyan entrepreneur whose food delivery app, Yummy, aims to drum up employment for women in her war-torn home country.

Yummy, co-founded by Nasser and her business partner, Azeeza Adam, gives women an online marketplace from which to sell meals: a kind of Uber Eats, but with homecooked food. Customers request a dish, and the app connects them with a cook who can prepare it in their kitchen, before linking them with a delivery driver.

Through Yummy, women can work from home anonymously, and take food orders from men without needing to interact with them. In Libya’s deeply conservative society, where security fears mean women are discouraged from working outside the home, it represents a socially acceptable way for women to earn a living from their kitchen.

“We wanted to help those women who have begun their own business from home, despite all of the obstacles they face,” says Nasser, “and to do it in a way that doesn’t require them to break social boundaries or be involved in an environment where security is poor.”

Just one in four Libyan women is employed, according to World Bank data.

Oil-rich Libya was once one of the wealthiest countries in the Middle East, but its economy has been beset by conflict and political division. Many households now struggle to survive on male incomes alone, so there is an increased economic need for women to work, says Nasser.

“There is no financial liquidity in Libya and most of the women can’t go out because of the restrictions – either social or security-wise,” she explains. “Things are getting harder.”

Nasser and her partner take 10 per cent of food sales made through Yummy, and 10 per cent of the delivery fee. In its testing phase, the app gained 500 cooks on its database, and 400 applications from potential drivers. But it faced a broader challenge in overcoming Libya’s patchy electricity and internet supply.

Nasser's wider goal is to formalise a home catering industry that has thrived since the war, and to help local women to expand their incomes. “Most, if not all of these women are in the grey economy,” says Nasser. “The country isn’t benefiting from their work, and the customers aren’t getting a product that is legally guaranteed.”

Yummy was initially self-funded, until in 2017 it was named as one of three winners of Libya’s first Enjazi competition – a joint venture between MIT Enterprise Forum Pan Arab and Tatweer Research designed to help diversify Libya’s oil-driven economy.

The resulting LD90,000 (about $65,000) impact fund took their ambitions to new heights: Nasser hopes to have around 600 cooks all over Libya in the first year, and up to 2,000 customers.

Looking ahead, sustainability is the aim: “so we won’t need more funds and it can be profitable while having a social impact,” she explains.

As the daughter of an activist – Nasser’s mother started the Women’s Union in Libya’s South – Nasser is driven less by profit and more by the app’s potential to support gender-based change.

"I was raised to go out and work," she says. "I wanted to provide that chance to other women. I’ve seen a lot of potential being wasted because of these restrictions."

“We encourage men to go out and build their own businesses and work for their money, but we try to keep our girls at home safe, and give them everything they need," she continues. "In my opinion, that’s not the correct way to build a healthy society.”

“There is no financial liquidity in Libya and women can’t go out because of the restrictions.”

Sneha Sheth — India

India has an education problem. While the world’s sixth-largest economy is succeeding in bringing children to school – around 100 million more are enrolled in education compared to a decade ago – dropout rates and learning outcomes remain abysmal.

“The scale of the problem is enormous,” says Sneha Sheth, co-founder of Dost Education, a US and India-based nonprofit which works to help low-income parents to take charge of their children’s education. “There are 150 million illiterate women and, by fifth grade, only half of children can read at a second grade level.”

India has more than 287 million illiterate adults – 37 per cent of the global total – according to a 2014 UNESCO report, and many experts believe that number should be doubled. In families where both parents are illiterate, and have no way to reinforce their child’s learning, students are less likely to learn to read and write.

It’s not a lack of motivation, explains Sheth; having had little schooling themselves, many low-income parents struggle to provide the early years’ support that forms the building blocks of a good education.

In 2015 Sheth founded Dost Education with Sindhuja Jeyabal, a fellow graduate student at UC Berkeley, in an effort to break this cycle of illiteracy. Backed with funding from the Mulago Foundation, its model capitalises on India’s surging smartphone usage to deliver educational podcasts to low-income parents, via phone call.

Short tutorials on topics such as heathy eating, picking out vegetables, and exploring concepts of shapes and sizes are aimed at helping parents of two to eight-year-olds tackle everyday parent problems, says Sheth, and “nudging them to turn regular moments into learning moments”.

“Since 90 per cent of our brains develop before age six, it means every moment in early childhood is a learning moment,” she explains. “Less literate parents may not have the time, resources, or exposure to support brain development during the early years, but the amazing thing is, a parent of any literacy level can do it. They just need a little support.”

Since launching in 2017 with 300 users, the learning tool is now being used by 30,000 families in Mumbai, Delhi and Bhopal. Sheth plans to scale Dost’s ‘phonecasts’ to reach one million families by 2021. “We’ll refine the model for deeper impact,” she says.

Dost users are typically mothers. Most have attained a high school education or less, and have household earnings of $1-10 dollars a day. The feedback from them has been particularly positive, says Sheth. Over 90 per cent of parents who sign up became active users of Dost's programme, and 70 per cent report that it has benefited their family.

“They tell us that Dost serves as a daily reminder and idea bank on how to build a positive relationship with their child.”

For Sheth, Dost’s value lies in its being able to offer more than just technology. The programme also tracks parents usage, knowledge retention and behaviour change during the 24-week course. But advances in technology and education in India are not yet in step, and Sheth cites persuading parents to invest their time in a new learning model as one of their major challenges.

Conversely, convincing donors of its impact was simpler. Mulago is joined by a team of backers that include US-based accelerator Y Combinator,

the advisory Gina's Collective and the Chintu Gudiya Foundation.

“Thankfully, we’ve found incredible funders who believe in the long-term vision,” says Sheth, though she acknowledges the challenges nonprofit startups face.

“We’re building a scalable programme, which means the early years require larger upfront investment,” she explains. “The nonprofit funding model is built around the opposite philosophy: give a lot of money to big organisations who have proven themselves, not small ones that are innovating in new problem areas.”

After 2021, Sheth hopes to work closely with state governments in India to integrate the most cost-effective components of Dost into the public preschool system. And in the meantime, buzz is building overseas.

“We’ve had a lot of interest coming from countries like Indonesia and Kenya,” says Sheth. "The Dost model can work anywhere, even outside of developing countries. But we’re focused on getting it right in India first.” — PA

“Since 90 per cent of our brains develop before age six, it means every moment in early childhood is a learning moment.”