Five doctors working on the frontline of disease elimination have each received up to $200,000 from Abu Dhabi’s Global Institute for Disease Elimination (GLIDE) to support new projects aimed at stamping out the last vestiges of polio, malaria, river blindness and lymphatic filariasis from their communities.

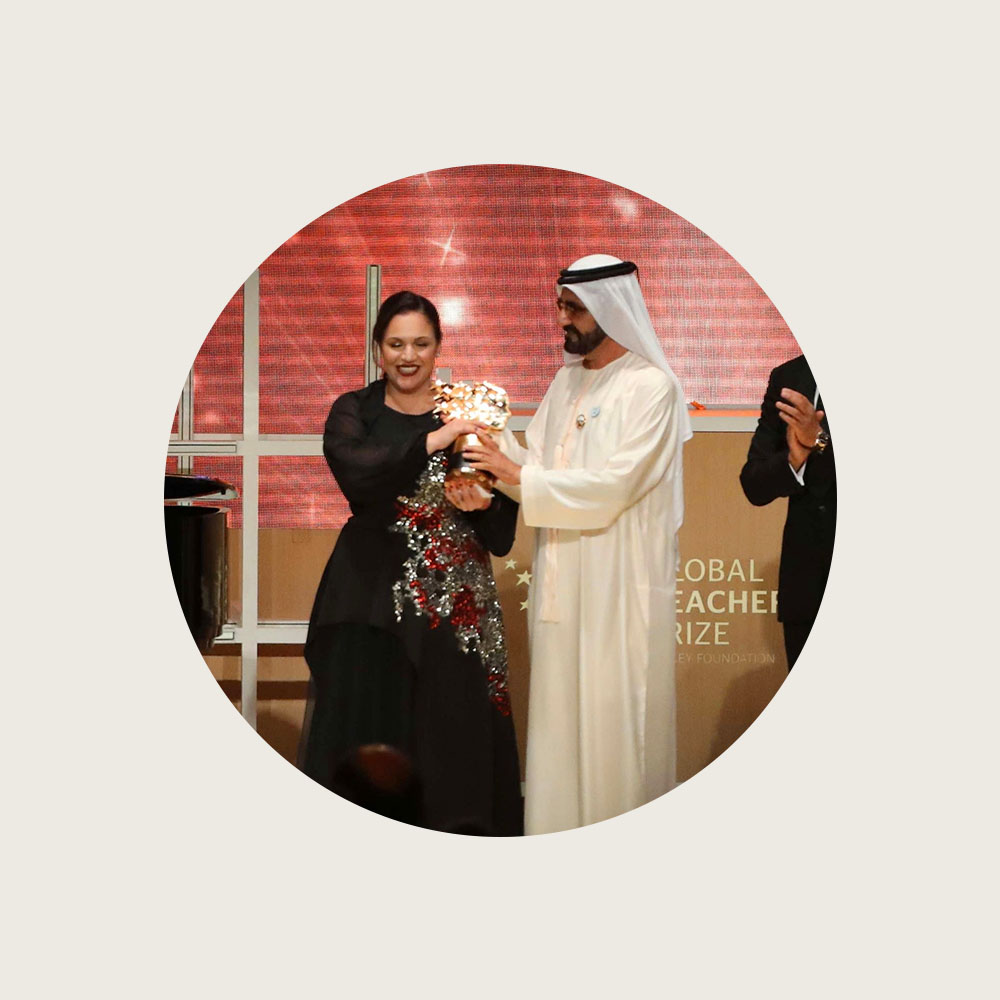

The recipients of the inaugural Falcon Awards for Disease Elimination - launched in April and unveiled at Expo 2020 Dubai - were chosen from a field of 220 applications from more than 40 countries.

Their submissions included: rapid polio testing for polio in Afghanistan and Pakistan; the mapping of river blindness transmission zones in Ghana; incentivising community leaders to promote polio vaccines; and extended and joint surveillance of malaria and lymphatic filariasis in the Philippines.

“Innovation is vital if we want to eliminate ancient diseases of poverty,” said Simon Bland, GLIDE’s chief executive officer. “The quality of applications we received from individuals and organisations based in disease-endemic countries, is testament to the will to consign these diseases to the history books. We just need to act on it.”